Tonantzin

madre de todo

lo que de ti vive,

es, habita, mora, está;

Madre de todos los dioses

las diosas

madre de todos nosotros,

la nube y el mar

la arena y el monte

el musgo y el árbol

el ácaro y la ballena.

Derramando flores

haz de mi manto un recuerdo

que jamás olvidemos que tú eres

único paraíso de nuestro vivir.

Bendita eres,

cuna de la vida, fosa de la muerte,

fuente del deleite, piedra del sufrir.

concédenos, madre, justicia,

concédenos, madre, la paz.

© Rafael Jesús González 2024

Tonantzin

mother of all

that of you lives,

be, dwells, inhabits, is;

Mother of all the gods

the goddesses

Mother of us all,

the cloud & the sea

the sand & the mountain

the moss & the tree

the mite & the whale.

Spilling flowers

make of my cloak a reminder

that we never forget that you are

the only paradise of our living.

Blessed are you,

cradle of life, grave of death,

fount of delight, rock of pain.

Grant us, mother, justice,

grant us, mother, peace.

© Rafael Jesús González 2025

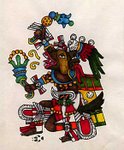

La virgen le dijo a Juan Diego que le dijera al obispo Fray Juan de Zumárraga que le levantara un templo en ese sitio y le llamara Guadalupe. Exigiendo prueba, el obispo despidió a Juan Diego. En una siguiente ocasión, Juan Diego se lo dijo a la señora y ella le pidió que piscara las flores que encontrara en el campo y se las trajera. En pleno diciembre en esa tierra árida americana Juan Diego milagrosamente encontró rosas de castilla en plena flor. Piscándolas y cargándolas en su burdo manto de fibra de maguey, Juan Diego se las trajo y ella las arregló en el manto y le dijo que las llevara al obispo Zumárraga. Así lo hizo Juan Diego y se cuenta que cuando se le admitió ver al obispo, soltó el manto esparramando las rosas y asombrosamente en el manto estaba la imagen de la virgen.

Es muy improbable que esto haya pasado. El señor obispo Juan de Zumárraga escribió extensamente pero en ningún de sus escritos se encuentra referencia a tal maravilloso hecho. Si sucedió o no, no es de gran importancia. Lo que se cuenta es que la señora le habló a Juan Diego en náhuatl diciéndole, "¿No estoy yo aquí que soy tu madre?" Pronto se formó el culto, la dulce Guadalupe Tonantzin reemplazó a la terrible Madre Diosa Coatilicue y sirvió para convertir a los indios en gran masa al cristianismo manteniéndolos dócil en esperanza de felicidad más allá de la muerte y sufridos en la esclavitud y opresión brutal por los conquistadores europeos.

Pero se rebeló la Guadalupana cuando en 1810 el cura Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla bajo su estandarte lanzó el grito de Dolores declarando la independencia de México. A lo largo de la turbulenta historia de México y Aba Yala (las Américas) hasta hoy, en la resistencia de los pueblos indígenas al cruel colonialismo capitalista es Nuestra Señora María de Guadalupe consuelo e inspiración.

En casi todo cuarto de mi casa cuelga una imagen de la Guadalupana inclusive la pintura del siglo 18 que colgaba sobre el altar hogareño de mi madre. Ella es lo femenino en la divinidad con la que Yeshua (Jesús) de Nazaret invistió a su dios patriarca. Ella es la raíz de nuestra revolución, que somos y que hacemos con la acción directa no violenta. Es la Tierra, la justicia y la paz.

[Nos vale recordar que el nombre María, nombre de las dos muyeres más importantes en la vida de Yeshua, su madre y la Magdalena, proviene del hebreo miryiam que significa “amargura” y “rebelión.”]

Barely ten years after the conquest of Mexico Tenochtitlan by the Spanish, it is said that in 1531 the Virgin Mary appeared to a converted Chichimec Indian named Juan Diego on the hill of Tepeyac, which some say was the site of a temple of the Mother Goddess of the Mechica, although there is no archaeological evidence of this.

The Virgin told Juan Diego to tell Bishop Fray Juan de Zumárraga to build a temple on that spot and name it Guadalupe. Demanding proof, the bishop dismissed Juan Diego. On a subsequent occasion, Juan Diego told the Lady about it, and she asked him to pick the flowers he could find in the fields and bring them to her. In the middle of December, in that arid land of the Americas, Juan Diego miraculously found Castilian roses in full bloom. Picking them and carrying them in his rough maguey fiber cloak, Juan Diego brought them to her, and she arranged them in the cloak and told him to take them to Bishop Zumárraga. Juan Diego did as he was told, and it is said that when he was allowed to see the bishop, he let go of the cloak, scattering the roses, and amazingly, the image of the Virgin appeared on the cloak.

It is highly improbable that this actually happened. Bishop Juan de Zumárraga wrote extensively, but none of his writings mention such a miraculous event. Whether it happened or not is of little importance. What is recounted is that the Lady spoke to Juan Diego in Nahuatl, saying, "Am I not here, I who am your mother?" Soon the cult was formed; the gentle Guadalupe Tonantzin replaced the fearsome Mother Goddess Coatlicue and served to convert the indigenous people en masse to Christianity, keeping them docile in the hope of happiness beyond death and enduring the brutal slavery and oppression of the European conquerors.

But Our Lady of Guadalupe rebelled when, in 1810, the priest Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, under her banner, raised the Cry de Dolores, declaring Mexico's independence. Through the turbulent history of Mexico and Abaya Yala (the Americas), in the resistance of Indigenous peoples to cruel capitalist colonialism, Our Lady of Guadalupe is comfort and inspiration.

In almost every room of my house hangs an image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, including the 18th-century painting that hung above my mother's family altar. She is the feminine in divinity with which Yeshua (Jesus) of Nazareth invested his patriarch god. She is the root of our revolution, which we are and which we carry out through nonviolent direct action. She is Earth, justice, peace.

[It is worth remembering that the name Mary, the name of the two most important women in the life of Yeshua, his mother and the Magdalene, comes from the Hebrew Miryiam which means “bitterness” and “rebellion.”]

-