Keynote address, 88th Annual National Poetry Day Banquet of the

Ina Coolbrith Circle (the literary society founded by

Ina Coolbrith, first poet-laureate of California in 1919), Oakland, California, November 3, 2007

Change

Change is always the theme of the poet, for he or she, more than anyone else, is, or should be, most acutely alive — and if life is anything, it is certainly change. After all, the very word verse means ‘turn’ and even to return means a change in direction. We often say of good poetry that it is universal and timeless, though all poetry from Gilgamesh through Shakespeare, to any contemporary poet one may care to name, sings change.

What is universal, timeless is the process of naming itself, Willy Shakespeare’s frenzied poet naming the airy nothings of imagination. It is the art itself that changes and orders chaos, Wallace Stevens’ jug standing in the middle of a wood in Tennessee, William Carlos Williams’ red wheel-barrow before a white picket fence — Adam assuming control of paradise by naming its parts, making out of the Earth a world.

And what, if not making a world, is the task of naming, of art, of poetry, the very word itself meaning to make, to create? Benedetto Croce has said that the poem being created is the poet him/herself, life, the world. Looking about us, we can in awe say, “What great beauty is the poet humanity capable of creating!” And at the same time we cannot help but say, “What a bad poet has humanity been!”

With words, with poetry, consciously or not, we create and change the world through naming and this naming must be conscious — and courageous. Right now, the world we have created overwhelms, threatens the very Earth that birthed us. To change this state of things, we must become much, much better poets (and who indeed is not a poet?) — more conscious of and awed by the beauty of this paradise that is the Earth; more compassionate of our ourselves, of one another, of all life that is the Earth — and more, much more, courageous in naming, naming those beauties, simple and complex; naming that loving of the Earth and the life she bears, naming those ills we must heal. We must change ourselves.

The task of changing, turning things about, creating a better world is ours, most especially ours who call ourselves poets, word-smiths, speakers of the culture, namers. We must sing our praises of the Earth more clearly and more loud; declare our love for one another and all life more passionately and strongly — and name those social ills that plague us with more definition and with more, much more, courage.

Those of us we call neo-fascists* (those gnawed by greed; those eaten by lust for power; those intolerant of differences; those hardened by unconscious or conscious fears; those quick for violence and cruelty) hold sway over our lives with their terrorizing and illegal wars; their torture; their suppression of democracy and its attendant civil liberties; their denial of bread, medicine, shelter, education to those in need; their onerous “Free-trade” coercions that benefit only the rich and rape the Earth; their violation of the Constitution that codifies our claims to justice and is the foundation of our law). By any definition of morality and of the law, the President of these United States of America, the Vice-President, and all their ilk are liars and criminals; and if we are truly honest, truly reverent of life and of the Earth, truly compassionate, truly courageous enough to be worthy of calling ourselves poets, we must name them for what they are.

Shelley has said that poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world. Then let us act as such, for our elected legislators for the most part are very far from being poets and most show precious little courage in defending democracy, the Constitution, humanity, the Earth — in naming things for what they are. I speak not of name-calling (the game of children and the tool of demagogues), but naming (the duty of the scientist and the poet); I speak not of choice but of obligation. In the service of the muses, goddesses of culture, in the service of the word of which the world is fashioned, there is no room for cowardice. We either speak truth or we do not, we either clamor for justice or we acquiesce to crime — if we do not speak truth, if we do not clamor for justice in a democracy, we do not merit the title of poets, much less of free men and women — and the gods save us, for then we refuse to save ourselves, not only from the gag, but from dishonor, and our demise. In a word, we must name things for what they are, do our part to change the world, to heal the Earth and realize the paradise, the only one we know, from which we were never expelled, but have, through strange and arrogant beliefs, mucked it up royally.

But even in questioning, naming, and speaking out for change, in the heat of righteous anger, never must we forego our joy, for it is the very root of our power. Our joy must be as righteous as our anger, rooted first of all in love, in love of the Earth, in love of one another, in love of life, in love of freedom, in love of all that is. Indeed, our anger is only righteous because our joy is compromised by the threat to and abuse of all that we love. (I would like printed a bumper-sticker reading “Don’t fuck with my joy!” and would do it were it not for fear of seeing it on a Hummer, its driver with a cell-phone glued to his/her ear, crowding me off the road.) And indeed much of my anger comes from the distraction of having to confront the “deathers”, the forces of death; I would much, much prefer to devote my poetry to the simple and joyous celebration of life, writing love poems. (But, hey, all my poems are love poems even those of protest; as I exhort in one of these:

---------let us be mirrors for one another,

---------& there let us sing our love-songs

----------------full of righteous anger

-------------------- & joy outraged.

---------------[In Protest of My Love: A Valentine; Farewell to Armaments;

----------------Mary Rudge, Ed., Estuary Press, Oakland, California 2003;

------------------------------author’s copyrights]

Joy must be what we most aspire to and Love its touchstone, touchstone of our beliefs. Indeed, our deep-shit trouble lies in that we humans have not yet learned to love enough. The most major change must be in ourselves. Writing on an archaic sculpture of the god of poetry and prophetic truth, Rilke could not avoid the conclusion: You must change your life.

There is the change we cannot avoid, the eternal movement of life that all poetry celebrates, the all-too-short trip from birth to death. And there is the change we need and must try to make. To do this we must first name things for what they are — to name things for what they are is first to see them clearly, even as Homer did though he was blind. To see things clearly also is an act of courage. We must question our own assumptions and beliefs; put them to the most stringent tests of love. We must question the very source of those beliefs. Descend to the very bowels of the past and question the ancestors:

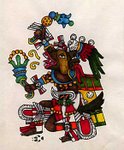

----------------— Señores míos, Señoras mías,

----------¿Qué verdad dicen sus flores, sus cantos?

----------¿Son verdaderamente bellas, ricas sus plumas?

----------¿No es el oro sólo excremento de los dioses?

----------Sus jades, ¿son los más finos, los más verdes?

----------Su legado, ¿es tinta negra, tinta roja? -

------------- Acepta sólo lo preciso:

---------------------lo que te haga amplio el corazón

------------------------lo que te ilumine el rostro.

--------------------— My Lords, My Ladies,

-----------What truth do your flowers, your songs tell?

-----------Are your feathers truly lovely, truly rich?

-----------Is not gold only the excrement of the gods?

-----------Your jades, are they the finest, the most green?

-----------Your legacy, is it black ink, red ink? —

-----------------Accept only the necessary:

------------------what will widen your heart

-----------------what will enlighten your face.

Only thus will we become, as the Nahuas said, masters of a face and a heart, in ixtli in yóllotl, enlightened poets worthy of the name.

© Rafael Jesús González 2007

Berkeley, California, November 3, 2007

*fas.cism n. 1. A philosophy or system of government that advocates or exercises a dictatorship of the extreme right, typically through the merging of state and business leadership, together with an ideology of belligerent nationalism. 2. Capital F. The governmental system of Italy under Benito Mussoulini from 1922 to 1943. [Italian fascismo, from fascio, bundle, group, assemblage, from Latin fascis, bundle. See bhasko- in Appendix.*]

The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language;

American Heritage Publishing Co., Inc. & Houghton Mifflin Company, publishers;

Boston 1979

*fas.cism (fashiz’m), n. [It. fascismo Webster’s New World Dictionary of the American Language, College Edition,

1968 edition New York; The world Publishing Co., publishers