Creation of the Sun and the Moon

from the sacred tellings of the Nahua

At the beginning of this world, when it was yet dark and darkness was everywhere, all the gods met at Teotihuacan (Place Where the Gods are Born) and they said, “It is not good that darkness should prevail; it is not good that there is no light. How shall the corn grow? How will humankind live?”

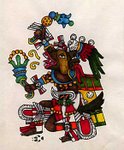

And they all agreed, “A Sun is needed; we must make a Sun.” So said Quetzalcoatl, Feathered Serpent, God of the Wind; and Tezcatlipoca, Smoking Mirror, God of the Night; and Tlaloc, God of the Rain; and Chalchihuitlicue, Lady of the Jade skirts, Goddess of the Waters; and Xochipilli, Prince of Flowers, God of Poetry and Song and Dance; and Chicomecoatl, Seven Serpents, Goddess of the Corn; and all of the other gods and goddesses too many to name.

So they said, “One of us must agree to be the Sun. One of us must leap into the holy fire to become the Sun.” And so they brought many precious woods, linaloe and caoba, oak and cedar, pine and mesquite, and built a huge fire that sputtered and hissed and sent a storm of sparks into the dark.

And they said, “Who shall it be? Who shall leap into the fire and become the new Sun?” And they all looked at one another and they were all afraid.

And from their midst stepped forth Tecuciztecatl, God of the Conch Shell, The Beautiful God, the most beautiful and the most rich, and he said, “I will become the new Sun.” And he walked through the crowd of gods and he was very beautiful to look at and he wore a loin cloth and cape of the finest cotton, soft as the tassel of new corn, embroidered with rainbows. On his head he wore a crown of the finest plumes: quetzal, macaw, hummingbird, parrot. Jade and turquoise adorned his throat.

He was a proud god and rich. His tools of sacrifice were of the finest. To prick his tongue, his ears, his penis for blood to offer to The Earth, Coatlicue, She of the Serpent Skirt, Tonantzin, Mother of all the gods and of us all, he carried, not thorns, but sharp slivers of coral. To catch the blood, he carried, not balls of grass, but balls of quetzal feathers. To offer perfumed smoke he carried only the finest of white copal.

And so he made sacrifice, four full days he sacrificed. He drew blood from his tongue, his ears, his penis with his slivers of coral and caught it in his balls of quetzal feathers and offered it to Mother Earth. He took his precious white copal and placed it on a live coal and sent the perfumed, white smoke into the skies.

Then he closed his eyes, took a deep breath, and ran toward the roaring, sputtering, fuming fire.

But the fire was too hot, too intense, too fierce. And he stopped short.

Again the Beautiful God closed his eyes, took a deep breath, and ran toward the blaze.

Again the pyre proved too hot, too fierce. And the god stopped short.

One time more, one more time, Beautiful God closed his eyes, breathed deeply, ran.

And stopped short.

And once again, one more time, again tried the beautiful god. And again could not.

The gods murmured among themselves and the Beautiful God was ashamed, for his heart had not been strong enough and he could not leap into the fire to become the new Sun. And the gods again asked themselves who among them would agree to become the new Sun.

And from far back, from the edge of the crowd of gods came forth the least of them, Nanahuatzin, the Ulcerous One, the ugly god, hunch-backed and crippled, his skin mottled with sores. And poor, he was. His loin cloth, his cape were of coarse maguey weave. His headdress was of amate paper. His tools of sacrifice were only black maguey spines. To catch his blood, he had balls of dry grasses. Too poor to afford even common copal, he had only chips of the bark. The gods murmured among themselves.

But he said, “I will go into the fire.” For four full days he said his prayers to the Earth; pierced his tongue, his ears, his penis with his thorns; caught the blood in his balls of grass; and offered them to the Holy Mother. He took his chips of copal bark, placed them on a hot coal and the feebly perfumed smoke rose to the skies.

He closed his eyes. He took a deep breath. He ran.

And,

------with his heart in his throat,

-------------------------------------he leapt into the fire.

The flames rose higher. They sputtered. They roared. They leapt. They sparked and they fumed. Sparks swirled up into the sky. Embers and coals shot out from the blaze. And the fire threatened to break its bounds, to lick its red and gold tongues into the grasses and shrubs of the land.

But, seeing this, the eagle swooped down from the sky and with its wings swept the burning embers back into the fire. But the live coals tumbled onto the grass and, seeing this, the jaguar scraped them back with his paws and rolled upon them to put out their flame. From that moment forth, the tips of the eagle’s wings are charred black and the skin of the jaguar is marked where he was burned by the embers.

The fire still rose, higher and higher. And for many days the gods watched and prayed not knowing from whence the Sun would come until the sky reddened in the east and from the center of the flames rose the heart of the least of the gods all ablaze and brilliant and flaming.

And it rose higher and higher and stood high and still in the middle of the sky.

The gods stood silent and amazed and they called him Tonatiuh, the Sun. And he burned fiercely and bright and his light was blinding and it became exceedingly hot.

The Beautiful God all this time watched from where he stood among the other gods. And a deep shame overcame him. And, taking heart, closed his eyes, breathed a deep breath, ran toward the fire —

----------------------------------and leapt.

The fire blazed and it rose and it fumed and it sputtered and sparked. And from its blaze rose the heart of the Beautiful God and became a second sun and stood close by Tonatiuh, the new Sun.

And the gods said, “This is not good. If there are two suns and both stand, burning so fiercely, in one spot, all upon the earth will be scorched and burned and the corn cannot grow and none of the animals, including humankind, will be able to live.”

And Quetzalcoatl, Lord of the Wind, said, “This is so.” And he put on his Wind Mask and took a deep breath and blew a hard wind that set the two suns moving across the sky.

And the gods were amazed and they said, “This is not good; it cannot be, for if we have two suns equally bright following so closely one upon the other, all will scorch and burn, wither and die.”

And Quetzalcoatl said, “It is so.” And seeing a hare hop among the grasses and the prickly-pears nearby, he ran after it, chased it down, caught it by the ears and, with all his might, swung it over his head and threw it at the second sun, hitting him round on the face.

Immediately the light of the second sun was dimmed and his flight slowed so that he followed a goodly pace behind Tonatiuh, the new Sun. And the gods said, “This is good. The second sun will be the Moon and he will follow the new Sun who will rule the day a goodly pace behind and light up the darkness of the night.” And it was so.

And because he was ashamed, the Moon had to make penance and atone for his pride and his lack of courage. So he fasts and when he does, he is seen to become, from his plump and beautiful self, thinner and thinner until he is a mere sliver, a shadow of himself. And then he breaks his fast and again grows plump and beautiful until he fasts again.

But even when he is plump and beautiful, one can still see the mark left by the rabbit where it struck his face long ago in Teotihuacan, where the gods are born.

© Rafael Jesús González 2007

[Commissioned by the Oakland Public Library, Oakland, California, while the author was Poet in Residence under the Writers on Site Program of Poets & Writers, Inc. and a grant from The James Irvine Foundation, 1996. Author's copyrights.]

No comments:

Post a Comment