Friday, September 30, 2011

Escritores del Nuevo Sol reading, Sacramento, California, September 28

-

Sacramento Press

Rafael Jesús González - activism and poetry amid costumes at La Raza Galería Posada

by Trina Drotar, published on September 29, 2011 at 11:24 PM

Wednesday evening was filled with poetry, music and activism when Rafael Jesús González (poet, professor, artist and bilingual studies innovator) read to a full house at La Raza Galería Posada. He was accompanied by flautist and Rooted in Community co-director Gerardo O. Marín and artist and activist Colin Miller.

The event was hosted by Los Escritores del Nuevo Sol / Writers of the New Sun and opened with local writer JoAnn Anglin. She spoke of the group’s founding in 1993, its monthly writing group, monthly readings and of the group’s anthology, “Voices of the New Sun: Songs and Stories / Voces del Nuevo Sol: Cantos y Cuentos.”

González was introduced by Dr. Fausto Avendaño, a retired Sacramento State foreign language professor, who explained that the evening’s reading would be bilingual. Poems, stories and introductions would be read in Spanish, and English versions, not translations, would follow.

The two men met many years ago, and Avendaño said González’s poetry resembled Federico García Lorca’s, and that “the images struck (him) because it is hard to equal García Lorca.” The idea González put forth that “poetry is just a game with words, images and metaphors” also reminded Avendaño of García Lorca.

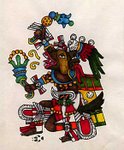

González read in front of a backdrop of swirling color, thanks to the current exhibit, “Ballet Folklorico-Lace and Ribbons: The Making of Cultural Affirmation-Costumes from the Instituto Mazatlan Bellas Artes.” He opened by burning a small leaf, a custom he performs before each reading, one that comes from his ancestors.

“We burn a little bit of fragrant smoke to invoke the gods so that what we say does not offend them or the audience,” he said, and suggested that politicians try this custom.

Judging from the full house that remained through nearly three hours, in a room that was often too warm, the sage-burning worked.

He began with a poem honoring Rosh Hashanah, the first day of the Jewish New Year. As with most poems, González provided some background. His third poem was one of his first published poems, and he says the topic is “as pertinent today as it was then.” The poem’s last line is “Señor, how much is this?”

To which he responded, “Too much. Far, far too much. Many of us were asked to give up our culture and our language to assimilate. We lost our names and took on English names to protect us from prejudices.”

Being an activist and a poet, many of the evening’s poems were politically charged. He read several poems about heroes like César Chávez, whose “voice will bear fruit and there will be rejoicing in the furrows, in the ditches.” He reminded the audience that “the battles of the fieldworker are not done,” and he urged people to remember the blood of those who died “when you say grace above your meal.”

Several nerves were touched when he read “To My Students,” with its memorable line of “You who can read, do not take it for granted.” Following the poem, he said that 1968 California “had the best education system in the country,” but that Proposition 13 (1977/78) “undermined the whole infrastructure of the state of California, and (he) quickly saw the literacy rate plummet.”

At the time, he was teaching at Laney Community College in Oakland, where the oldest student was 79 and the youngest was 18, and where “real education was taking place.” Today, he says that it is “to our shame that the wealthiest state cannot afford to teach its children” and called "No Child Left Behind" the most anti-education act.

Poems about the Golden Gate Bridge, houses, and jade hearts preceded more hero poems. One was about Víctor Jara, one of the imprisoned intellectuals in post-Allende Chile. “The Hands” relates the near-myth story of Jara’s hands being severed by guards, and the refrain of “each drop, a note against silence” served as a reminder for each of us not to remain silent.

Perhaps the most touching of González’s poems was “Blankets,” written for “my mother (who) still covers me with rainbows.” This piece, as with a few others, was accompanied by Marín, who played two different native Mexican flutes.

The music served to make González’s voice stronger, and it seemed to work better with the Spanish readings. But Marín, who always watched his maestro, never overpowered the words.

Following a poem written as part of his dissertation about the influence of the gypsy idiom on García Lorca’s work, he spoke about living and writing.

“Everything we do is a game,” he said. “Living is a celestial game that is sometimes peaceful, sometimes difficult. Sometimes words are very volatile. To name a thing can take away its power, (and that) gives us power over nature.” He called naming a “sacred act.”

About writing, González said, “Everybody can write.” He urged the audience to “write for fun. Write for the music of the words. Write to overcome your pain. Write to celebrate your joys.”

He closed with “If We Do Not Speak,” influenced by his invitation to the 20th World Congress of Poets in 2005. While driving home from Santa Fe, N.M., he considered what he wanted to tell his fellow colleagues who spoke in many languages. The opening line is “If we do not speak to praise the Earth / It is best we keep silent.”

He closed with a reminder that “we have never been expelled from paradise. We live in paradise,” and that we “need to care for and love the earth more.”

-

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment