It is twenty-five years ago that, for a long time knowing that the only thing we have is the Earth, I took a year leave of absence from my academic duties to work with the Livermore Action Group (a loose organization/network that organized protests at Livermore Nuclear Weapons Laboratories and elsewhere from 1982-1985) to organize the First International Day of Nuclear Disarmament.

On January 24 we undertook the first direct action of the year with a blockade of the tests of the MX nuclear missile in Vandenberg Air force Base where I was arrested with hundreds of people who trespassed upon the base to impede the tests in an act of civil disobedience.

It was on this day in the detention center of the base that I wrote the poem ‘Here for Life.’ The narrative of my experience of the blockade was commissioned by the magazine Good News, a publication of the Laney College faculty.

-

------------- Here for Life

-----(Vandenberg Air Force Base, January 1983;

---------first blockade of MX Missile testing)

I am here —

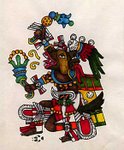

I wear the old-ones’ jade —

it’s life, they said & precious;

turquoise I’ve sought to hone my visions;

& coral to cultivate the heart;

mother of pearl for purity.

I have put on what power I could

to tell you there are mountains

where the stones sleep —

----hawks nest there

& lichens older than the ice is cold.

The sea is vast & deep

keeping secrets darker

than the rocks are hard.

I am here to tell you

the Earth is made of things

so much themselves

they make the angels kneel.

We walk among them

& they are certain as the rain is wet

& they are fragile as the pine is tall.

----We, too, belong to them;

they count upon our singing,

the footfalls of our dance,

our children’s shouts, their laughter.

I am here for the unfinished song,

the uncompleted dance,

the healing,

the dreadful fakes of love.

----I am here for life

--------& I will not go away.

----------© Rafael Jesús González 2008

Vandenberg Air force Base: January 24, 1983

*----*----*

At the van, Linda and Kelly pin the yellow blockaders’ arm-bands to our sleeves; mine goes on the left arm so it won’t cover the Lifers’ (our affinity group’s) emblem on my right sleeve. I put Andrew’s money in my wallet, give the wallet to Brian; Kelly keeps my watch, David takes my keys. I decide to use the name Ignacio Peña after the protagonist of one of my short stories. I tell everyone my arrest name.

At the van, Linda and Kelly pin the yellow blockaders’ arm-bands to our sleeves; mine goes on the left arm so it won’t cover the Lifers’ (our affinity group’s) emblem on my right sleeve. I put Andrew’s money in my wallet, give the wallet to Brian; Kelly keeps my watch, David takes my keys. I decide to use the name Ignacio Peña after the protagonist of one of my short stories. I tell everyone my arrest name.We arrive at Vandenberg and congregate on the grass by the road across from the main gate; the television trucks and cameras (the TV stations’ and the air force’s) are there; so are the blue meanies, the yellow meanies, bright and mean-looking, large sticks in hand, lined up, feet apart, the washed-gold light glancing off the plastic visors raised on their helmets. The air force troops are there also, their huge black boots newly polished or wet (probably both), cracking-clean, olive-green trousers bloused over tightly laced ankles, clubbed, helmeted, in formation, feet apart, threatening. We form a large circle, Andrew and I next to each other, arms around each other’s shoulders. The TV cameras (especially the air force’s, I note) scan us. We look around, at the opposition, the media crews, the crowd of protesters at the gate. I see Fran behind us wearing her red monitor’s band on her forehead; boy-handsome John (lover of my blind former prize student Ana María) hugs me and joins our circle for a few minutes. He is warmly greeted; lovable, committed, a hard worker, of a dazzling, sometimes infuriating innocence (the one caught on the base with maps and Livermore Action Group literature in July.) We sing; the sound is strong, sweet against the morning air, joyous; the sticks of the meanies are hard, but true power is our joy, our song; yes, the flower is the true symbol of life. “We shall overcome.”

We have to decide where we shall go over the line onto the base, at the gate or further down the road into a field. Much discussion; where will we be more effective, more visible to the media? Which will enhance our own empowerment? Which will allow us to act, which force us to react? Where will we be more creative, less committed to the expected? Again a stalemate; we are unable to reach a consensus. We agree to walk across the road to the gates and get more information, look things over. The monitors guide us; we’re careful and watch the traffic lights closely as we cross the road; we don’t want to be arrested for something silly like walking a yellow light.

We skirt the crowd at the gates, talk to people. We’re told to sign up at a nearby table with Starhawk; Brian has the list of our names so we let him take care of it. We form our circle, Andrew and I close together, behind the crowd; more discussion pro and con, the gate, the field. The gate has the attention of the media, TV cameras, reporters all around, more guards, too; in the field, troops are strung out, a large space between each soldier; even at that, the line does not go far, but no cameras, nothing is going on there. We take a straw vote; we’re perfectly divided, even the Lifers: Andrew is for the field, I’m for the gate. I suggest half in jest that we toss a coin; the suggestion is taken up. Joaquín, a young boy of ten, the youngest member of our cluster Change of Heart present, is handed a nickel. Andrew would have liked to have used the good-luck New York subway token his father gave him, but it’s too late; Joaquín has thrown the glinting nickel into the air. It lands on the grass soundlessly, bright and pure: tails, the field. (The gods are with us; those who opted for the gate were treated more roughly, got heavier charges, sentences from the state.) Brian goes to alert the media that something is about to happen. We sing songs as we wait for the TV crews to arrive.

We break up the circle when we see them come, walk in threes down the shoulder of the road minding our p’s and q’s; we don’t want to step into the road or onto base property before we’re ready. Andrew laments having left in David’s car the bunch of yellow daisies his friends from the Draft Resistance gave him before he left. On the other side of the wire fence the soldiers run to follow our movement, become more straggled. We sing as we walk, arms around each other.

We reach our spot, well away from the gates; the troopers on the other side of the fence scurry; the TV crews are behind us. We hug and kiss those who will remain behind as our support faction. The Lifers form a tight circle, arms tight about each other. Joaquín brings out a white wax candle he has made; we are to light it for a final blessing. Will, the boy’s father, has trouble lighting it in the restless breeze. We all shield it; it lights, the flame bright and steady. Andrew and I both hold it; my heart is full. Will places his hands over and beneath ours. A silence, the world is us. I recite the opening blessing of the puja; my voice is clear, resonant, full in the morning light; it is only the second time I’ve said the blessing in public. The first was when I laid the stone of purity in my first medicine wheel. The ancient Sanskrit resonates like deep-throated bells against the eucalyptus, the final avahanam a pearly hum in the air. Kelly echoes it. We put out the candle, kiss one another one last time, join the other blockaders, lock hands, and walk toward the fence.

We jump the fence, run out onto the field, join hands once more and form our circle; we sing, fully, clearly, with all our hearts, the pits of our bellies. From the fence, our people join us. The soldiers don’t seem to know exactly what to do. Someone barks an order at them and they yell for us to stop. We continue, never breaking our circle, our song. They run up to us, stand feet apart behind us; our circle stops only when the bodies of the soldiers themselves stop us. My back is pressed closely to the chest of the soldier behind me; I can feel his warmth through my jacket, I can almost swear I feel the buttons on his shirt. When we stop, the soldiers step back. We continue to sing, in love with one another and the world; for the first time since coming to Vandenberg, I feel fully empowered. I’m here for life, for my friend whose hand I hold, for my family, my friends, those whose lives I have touched, those whose lives I will never touch, for every ineffably marvelous, precious form life takes in sea, air, land, every squirming sliver of life, the greenness of leaves, for this holy planet I will never be able to fully know, for love, for life.

We jump the fence, run out onto the field, join hands once more and form our circle; we sing, fully, clearly, with all our hearts, the pits of our bellies. From the fence, our people join us. The soldiers don’t seem to know exactly what to do. Someone barks an order at them and they yell for us to stop. We continue, never breaking our circle, our song. They run up to us, stand feet apart behind us; our circle stops only when the bodies of the soldiers themselves stop us. My back is pressed closely to the chest of the soldier behind me; I can feel his warmth through my jacket, I can almost swear I feel the buttons on his shirt. When we stop, the soldiers step back. We continue to sing, in love with one another and the world; for the first time since coming to Vandenberg, I feel fully empowered. I’m here for life, for my friend whose hand I hold, for my family, my friends, those whose lives I have touched, those whose lives I will never touch, for every ineffably marvelous, precious form life takes in sea, air, land, every squirming sliver of life, the greenness of leaves, for this holy planet I will never be able to fully know, for love, for life.The soldiers behind us are young, almost boys; they look scared. We smile at them, try to assure them we are not here to hurt them. We open our circle and ask them to join us, offer them our hands. They look sheepish, embarrassed, or confused, some (not too convincingly) belligerent. We take up “We shall Overcome” — strongly, clearly, bring our words out from deep within us, full with the stuff of life. A knot forms in my throat so large I have trouble letting the words out; I don’t hold back the tears. Andrew looks at me. The Lifers, Change of Heart are singing with us from the other side of the fence. They blow us kisses and wave peace signs; we blow kisses to them and wave back.

Even as I point, Andrew sees the red-tailed hawk that hovers low, sensuously, nobly above us, undulating as it rides the air, my nagual, my medicine bird. We recognize the blessing; we are touched by the god. Everyone looks up, the whole circle, the Lifers and Change of Heart by the fence, the soldiers; Joaquín is excitedly pointing to the bird. It just hovers there. Brother Hawk is in no hurry; he circles once more, slowly, then, satisfied and with great dignity, wings his way back across the fields toward the hills.

Cameras click around us; TV cameras whir. Activity among the troops behind us. Reinforcements arrive, these with visors on their helmets, large clubs in their hands. Scurrying to the right of our circle, other affinity groups, clusters, have followed us onto the field. We are jubilant; we want to dance; we circle around and sing, ”Vandenberg is falling down, Vandenberg is falling down, no more MX.” The people by the fence go wild with glee. We stop our circle, grinning, a little breathless.

Then we begin the Tibetan chant for peace — na-mu-myo-ho-ren-ge-kyo — over and over again; I’m sure the hills feel it deep in their roots of stone. I am particularly conscious of Patrick’s voice; it reverberates, quivers as it enters my gut. Movement among the troops behind us; growled orders. A man directly behind me takes up a bull-horn, the sound loud and harsh; he reads us the ordinance we’re breaking, the charges we’re incurring, the penalties we’re subject to, our rights. He reads fast, running the sentences together, without inflection, in a monotone, perfunctorily. We do not break our chant; we raise our voices so they rise above the strident croak of the bull-horn. He has nothing to say to us; we are singing to the gods. He finishes his say. “Na-mu-myo-ho-ren-ge-kyo,” over and over again, slow, sustained, resounding, one last time, the final kyo sustained, reverberates in the air. It follows the path of the hawk into the hills. We are silent even after the last echo completely fades away.

A bus comes onto the field, disgorges a group of helmeted, visored troops who run toward us. We take up another song. The group of trespassers to our side nearer the gate are being taken away two by two; there are four arresting soldiers, two per person arrested. The four then come back for two more; it will take them a long time to arrest us all. The people at the fence cheer; cameras are still clicking, whirring. We sing.

It’s our turn; four soldiers come to us and take two of our comrades; we ask them to be gentle; they walk off with our friends. We cheer along with our people by the fence, close ranks, continue singing. The soldiers come back for two more; they are young, unsure, almost apologetic, say “please” and call us “sir” and “ma’am.” At the fence more cheers and blessings. We continue singing.

Two more are taken away; the arrests are random. Two by two our circle

keeps growing smaller; the soldiers walk toward Andrew and me, vacillate, then take someone else; we hold tightly to each other’s hands.

keeps growing smaller; the soldiers walk toward Andrew and me, vacillate, then take someone else; we hold tightly to each other’s hands.At last only Andrew and I are left. The Lifers at the fence are wild with joy. Will later tells us that here Joaquín cried for the first time. We face one another and hold hands, our circle of two. We look at each other and smile. We try to continue singing; neither of us can carry a tune. The world is us.

The soldiers come for us. They are courteous to me, gentle. I think I should say something wise, something pithy to them; my mind is blank. All I am conscious of is the greenness of the grass, the hold on my arms, the cheering in my ears, the sun, the newly washed air. In the cheering I hear the Lifers cry, “We love you!” I glance at Andrew away to my left between his two soldiers; he is talking to them. I can’t tell if they’re hurting him; I assume they are not. Later, I find I am wrong; one soldier, the young one, is gentle; the other, a sergeant, is not. When Andrew tells him to consult his conscience, not to blindly carry out orders and rules, he answers, “If I had my wishes I’d break your arm.”

*----*----*

At the buses near the main gate, blockaders are being loaded. Donna of the Non-Nuclear Family is dragged in; she has gone limp and three soldiers tug, pull, heft her onto the bus. Her arms are being twisted behind her; she grimaces in pain. One of the soldiers is particularly rough and her wrist has been hurt, sprained. We tell the soldiers, “Be gentle, be gentle,” and chant, “Shame, shame, shame.” They seem both embarrassed and belligerent at the same time. We comfort Donna; the bus starts to move off; the crowd at the fence cheers us; we hang out the windows and cheer back, wave to the Lifers.

At the buses near the main gate, blockaders are being loaded. Donna of the Non-Nuclear Family is dragged in; she has gone limp and three soldiers tug, pull, heft her onto the bus. Her arms are being twisted behind her; she grimaces in pain. One of the soldiers is particularly rough and her wrist has been hurt, sprained. We tell the soldiers, “Be gentle, be gentle,” and chant, “Shame, shame, shame.” They seem both embarrassed and belligerent at the same time. We comfort Donna; the bus starts to move off; the crowd at the fence cheers us; we hang out the windows and cheer back, wave to the Lifers.One young woman is our bus driver, another is one of the MPs. Another guard is a young black

man. We sing; one of our songs is “We Shall Overcome.” I wonder if he remembers it from the Civil Rights Movement. There is much talking among us; we introduce ourselves by our arrest names. Someone passes out vitamin C pills so sour they curl the tongue. A man admires the embroidery on my jacket, says it is the most beautiful he’s seen. I am proud of my embroidery, pleased when it is admired. Many people have commented on it. I notice that women most often ask who did it for me and show surprise when I say I did. Female chauvinism?

man. We sing; one of our songs is “We Shall Overcome.” I wonder if he remembers it from the Civil Rights Movement. There is much talking among us; we introduce ourselves by our arrest names. Someone passes out vitamin C pills so sour they curl the tongue. A man admires the embroidery on my jacket, says it is the most beautiful he’s seen. I am proud of my embroidery, pleased when it is admired. Many people have commented on it. I notice that women most often ask who did it for me and show surprise when I say I did. Female chauvinism?*---- *---- *

The bus stops at a field and waits. Finally, after a long time, a young, tough-looking MP leading a stocky, mean-looking, black German shepherd boards the bus. He acts belligerent, speaks in a loud, tough Southern accent.

He says, “You are to go with me three at a time. The dog is dangerous and will attack not only you but me if you resist, attack me, try to run, or act froggy.”

To act froggy is our last intention. We go with him three at a time. The blockaders in the other bus cheer us warmly.

He takes us around to the back of a gym and turns us over to other MPs. Letters of the alphabet are written on the back of our hands with broad, black, felt-tip pens. I get a large P. We pass an MP who looks Chicano, whose name tag-bears a Spanish surname; “¿Qué haces aquí, 'mano?” I say. His face is set, abashment barely discernible behind it. He looks past me. We are led across a lawn to a square, smaller building with a low, narrow door we have to stoop to enter. It’s a handball court.

Each trio that comes in is hugged and welcomed warmly by those already there. It’s cold in the court; when the last from our bus has come in, we form our circle and sing. Then we break up into groups talking, sitting around. Andrew insists that I write my journal; I don’t want to, but I take out my pen and tiny black and red notebook and start writing. A discussion has started about prejudice, racial and otherwise; it grows heated, everyone joins in, forms a large circle sitting on the floor. Except me; I have to choose between the experience or the recording of it. I want to join in, put in my say, but I continue writing, sitting with my back against a cold wall. Many people look my way, expectant, inviting, giving questioning glances. It occurs to me that except for a person or two of Asian extraction, I am the only distinctly recognizable member of a racial minority here.

The discussion ends. Groups form; a few of the men roll up a pair of socks for a ball and kick it about the court. People sit on the floor or stand around talking. When we need to use the toilets, an MP just outside the door escorts us. Some of us go in the hope of seeing another blockader who was arrested before us; we want to know, need to know what is happening so we can form some kind of solidarity with them.

We wait and wait. I move from the wall easily seen by the guards and sit in a corner on the other side of the door; I’m thinking of smuggling my notebook and pen into jail and I don’t want them to notice me writing. People respect my privacy; Andrew comes to check on me, squats in front of me. I’m grateful for his checking.

*---- *---- *

We wait some more; we must have been here two hours. We’re cold and hungry. I have eaten only a chocolate chip cookie, a bite of sandwich, a bite of a brownie, and a vitamin C pill.

We have heard that a group of trespassers has penetrated to the very silos. We are jubilant, but worried for them. Our solidarity must protect them. The guards call for us by the letters on our hands, one by one; a slow process. I sit down to more jotting in my notebook. The big, burly, red-headed, red-bearded guy who passed out the vitamin C and was so loud in the discussion of prejudice starts to bang hard on the walls. The sound is loud and unpleasant; I wish he’d stop.

When the Y’s have all left the court, they start with the P’s. I put my writing away. One of the MPs comes for us wearing surgical gloves; I imagine strip searches, obscene, humiliating treatment. Andrew is taken away. The wait is long. A soldier comes for me and leads me across the small lawn into the large gym; the court has been divided into rooms by partitions. He orders me to stand at a white line just inside the door, then leads me to a desk where a young black woman asks for my ID; I have none. She writes “John Doe” at the top of the form. Then she says, “What is your name?”

“Ignacio Peña, “ I say.

She writes it down, making complete hash of it even though I spell it for her several times. I can’t give her my social security number; even if I wanted to, I can never remember it. I start to give her a fake place of birth but decide it’s not worth the trouble. The rest of the information I give her is correct: birth date, address, etc.

Then I’m taken to the next table where a young airman (the air force must have few career men; almost all of them are so young) sits behind a typewriter. I glance behind me and see Andrew take off his jacket and possessions and place them on the floor at the feet of a sergeant wearing surgical gloves. I feel a surge of anger at this threat of a strip search. The clerk goes over the form from the previous desk; I insist on the correct spelling of Ignacio Peña. “That must be Spanish.” he says, and gets it wrong anyway, placing the tilde over the a.

Next I’m taken to a cubicle behind me to stand before a camera. I make the most grotesque face I am able to.

“Is that the way you want to look?” the young man behind the camera asks with an amused smile.

“Yeah,” I grin at him. Then on to the next cubicle where I had glimpsed Andrew; he is now standing before a table, his possessions between him and the young airman sitting behind it. We nod and smile. The sergeant with the rubber gloves tells me to empty all my pockets on the floor. He takes the refraction pins from my jacket, the small safety pin which holds my blockader’s arm-band to my sleeve.

“No sharp objects,” he says. Afraid I’ll put out my eyes, maybe. He says I can keep the arm-band. I fold it and put it into a pocket of my jacket. He tells me to take off my jacket and lay it on the floor. I lay it down carefully (the embroidered plumed serpent on the back and the heart-and-lotus of the Lifers’ emblem on the sleeve are beautiful indeed.) We have agreed to resist strip searches; however, I am only frisked.

“Have you placed everything on the floor?”

“Yes.”

“Spread your feet and place your hands above your head on the wall.”

I’m a little uneasy; if he finds the small nail clippers I have kept to cut the plastic handcuffs should I get them, I’ll just say I overlooked them. He doesn’t detect them.

Then to another table in the cubicle behind me. A pretty black woman is clipping my mug shot to my forms; she grins. In the photo my face grimaces grotesquely above a card reading P-9.

She laughs and asks, “Would you like a copy to send your mother?”

“Yes,” I answer, “I sure would.”

On to another cubicle for finger-printing. Just before leaving the handball court I rubbed my forefinger and thumb on my nose and the back of my ears to oil them and Andrew offered me some dirt to rub so that the prints would smear; not much good. Practically the whole palm is printed. The guy is courteous, gentle, making little jokes.

“Relax,” he tells me. “I’m only doing my job, and my work is to protect you.” Maybe he means from being in the air force!

“My work is like yours,” I say. “I am here to protect you. Nuclear bombs don’t discriminate.”

“Sign the finger-print card, please,” he says.

I sign, “Ignacio Peña.”

Another MP ties my wrists with plastic handcuffs before leading me to another cubicle, before another camera. Two pretty white women soldiers take the mug shots. Almost all the women are pretty, the men handsome — does the air force recruit for good looks? I’m sure the kindness and respect they all show me adds to their attractiveness. This time front and side views are taken; for both shots I make a face. The young women laugh. I wish I could see how these turned out.

Then I am taken to the holding area at last; it is a long, narrow room on the side of the gym; one wall is chest-high with chicken-wire the rest of the way to the ceiling. Many of our friends are there. I see Andrew sitting on a bench against the opposite wall. I sit down and easily slip one hand out of the handcuffs. I take out my clipper and start snipping the cuffs off other blockaders. Some of us have metal ones we can do nothing about. We make circles so we won’t be seen through the chicken-wire. Others warn us when an MP approaches. We keep our hands crossed at the wrists as if we still had on the cuffs, a needless precaution. The MP doesn’t seem to care whether we have cuffs or not. Two hundred already arrested, two hundred handcuffs at a dollar apiece; that’s two hundred dollars that won’t go to make nukes. It won’t go for food, but it won’t go to make nukes.

* -----*---- *

Time drags. I go to the chicken-wire and watch the MPs, the women in khaki dresses, the men in their black boots and bloused, olive-green fatigues. The interaction between them and the blockaders is cordial, easy; apparently, they feel some affinity toward us. After a while some MPs come in with a large cardboard carton of box lunches. We’re happy to get them; we’re ravenous. Two sandwiches, white bread, one of American processed cheese and a slice of pallid baloney and one of what tastes like peanut butter but looks like dark rubber cement. Also an apple and a pint of milk. The soldiers insist that this is the same stuff they eat. They must say this to make us feel better; if it’s true, they may die of malnutrition before the nukes get them. There aren’t enough to go around so we share; more blockaders are coming in and we divide the goodies with them, too.

*----*----*

I go back to the chicken wire where a blockader has struck up a conversation with a handsome, stern MP. I give him a smile, open and without malice. He thaws a little, gives me a little, shyly ironic smile. I can see his name-tag: Stephens. He says he hasn’t had any sleep in twenty-four hours. Says they’ve been overworked preparing for us. I tell him that from our side, we’ve also overworked coming here. I would have liked to talk with him more, found out more of what goes on the other side, but now the P’s are being called.

At the door, I ask the MP, “How long will it be before I am called?”

He consults his list. “You’re at the top of the list. You’re next.”

A few moments later someone walks up to him, tells him something, and I am called.

Outside, a sergeant hands me my notice, my diploma, and says, “Read it and sign here.”

“I know what it says, and I won’t sign it,” I answer.

A map of the base is attached to the notice (so we’ll know where to go when we come back in March?) He gives me the original and says, “Follow that MP down the hall.”

“I’ll see you in March,” I say, tucking the notice in my pocket. The hall is strewn with cut plastic handcuffs.

*---- *---- *

It is nearing midnight. We are boarded on a bus, and as we drive through the darkness, I am quiet and look out the windows at the darkened fields, the hills. We speculate about where we will be taken, how we will get back to our homes. The other Lifers should have already struck camp, headed back to San Francisco Bay for work tomorrow. Maybe Andrew and I can catch a bite to eat somewhere and take a Greyhound bus to Oakland. After a good distance we stop, just beyond a gate, the middle of nowhere. A sergeant reads off the ban-and-bar orders, tells us we are never to return. We assure him, “We’ll be seeing you in March.”

As I walk toward the door of the bus, I pause and kiss the pretty MP. She is shy; she smiles modestly. The man beside her is trying to look stern, but his mustache twitches in a suppressed smile.

“You don’t get one,” I tell him.

“That’s all right,” he says.

I give him a blessing.

* ----*---- *

© Rafael Jesús González 2008

-

(Good News; a Publication of the Laney College Faculty;

Vol. 7 Spring 1983; Oakland, California; author's copyrights)

Vol. 7 Spring 1983; Oakland, California; author's copyrights)

-

No comments:

Post a Comment