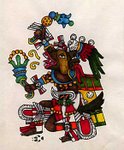

To celebrate César E. Chávez,

the eulogy written on the occasion of his death 15 years ago.

the eulogy written on the occasion of his death 15 years ago.

---------A fines de abril

-------------------------a César E. Chávez

A fines de abril

las viñas ya verdes de brotos,

llegó la muerte al campesino,

al césar de las uvas vestidas de azul,

de las cebollas de fondos blancos,

de las manzanas de vestiduras rojas.

-----Le dijo — ¡Vén, César! —

Y se lo llevó de las uvas envenenadas,

las sandías, los melones llenos de mal,

de las batallas de los surcos,

de las emboscadas de las acequias,

del estandarte guadalupano,

de la bandera roja y negra.

Pero en los surcos

su voz dejó sembrado

su anhelo por justicia —

---que es decir reclamar

--------el pan para el hambre

--------el alivio para el enfermo

--------los libros para el inocente.

Su voz dará fruto

---y habrá regocijo

------en los surcos,

------las acequias,

------las mesas,

------la tierra.

-----------© Rafael Jesús González 2008

(Siete escritores comprometidos: obra y perfil; Fausto Avendaño, director;

Explicación de Textos Literarios vol. 34 anejo 1; diciembre 2007;

Dept. of Foreign Languages; California State University Sacramento;

derechos reservados del autor.)

----------At the End of April

------------------------to César E. Chávez

At the end of April

the vines already green with buds,

death came to the field-worker,

to the caesar of the grapes dressed in blue,

of the onions in white petticoats,

of the apples in red vestments.

-----She said to him, “Come, César!”

And took him from the poisoned grapes,

the watermelons, the melons full of ill,

the battles of the furrows,

the ambushes of the ditches,

the Guadalupe standard,

the red and black flag.

But in the furrows

his voice left planted

his longing for justice —

----which is to say, his demands

-----------for bread for the hungry,

-----------healing for the sick,

-----------books for the innocent.

His voice will bear fruit

-----and there will be rejoicing

----------in the furrows,

----------in the ditches,

----------round the tables

----------in the land.

----------© Rafael Jesús González 2008