City

City

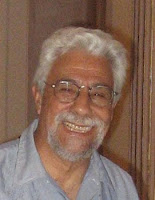

City of Berkeley Honors Poet & Artist Rafael Jesús González

Tuesday, October 13, 2009, 7 p.m. Berkeley City Hall Council Chambers at Martin Luther King Jr. Way between Allston Wayand Center Street in downtown Berkeley

An old hand-bound, brown leather book contains the poems that his mother, Carmen, typed and read from when he was a boy. Its pages are yellowed and thin but contain poems that he has loved all his life by classical Spanish and Latin American poets: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Juan De Dios Peza, Gabriela Mistral, Amado Nervo, and Rubén Darío among others. This early contact with literature meant that Berkeley poet Rafael Jesús González has “been writing all my life.”

On October 13, at 7 p.m. in Council Chambers, the City of Berkeley will honor González for his contributions to the local community. For someone who describes himself as “something of a hermit,” González has long been active in progressive politics and the creative arts throughout the Bay Area. His political passions are focused on environmental and social justice issues, while a career in writing and literature has inspired many others to use their pens for both personal expression and political action. But, González is also a visual and performance artist. For many years, he has been the elder in a Latino men’s ritual group, Xochipilli, which sets the ceremonial tone for Oakland Museum of California’s annual Día de Los Muertos festivities. González has contributed several art installations to the museum’s “ofrenda“ displays marking the indigenous celebration, also creating installations for the Mexican Museum and the Mission Cultural Center both in San Francisco.

Although he grew up in a house full of books, his path into the arts was somewhat indirect. Born and raised in El Paso, Texas, González had a military career at first, serving in the Navy’s hospital corps and as a staff sergeant in the Marines. He attended the University of Texas, El Paso, on the G.I. bill and took a pre-medicine degree, majoring in both English and Spanish literature with minors in psychology and philosophy. Around that time, he realized he “loved literature best,” and switched gears, receiving a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship and a National Education Act Fellowship to the University of Oregon to pursue a career in education. González taught literature, English composition, and creative writing, first at the University of Oregon, then at Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado, Central Washington State University in Ellensberg, Washington, “where it snows a lot in winter,” and finally coming to the Bay Area where he taught at Oakland’s Laney College for 30 years.

He retired in 1998, in part because the increased illiteracy of his college-age students made his job harder though less challenging. “Grading became more of a chore; class sizes were larger.” Students were entering college without the rudimentary skills in reading and composition. He lays this problem at the doors of those who promoted and passed Proposition 13 (the 1978 tax revolt which massively reduced public school funding). As an instructor “there was less time to comment on logic and the development of an argument,” and an increased need to focus solely on punctuation and sentence structure. After leaving Laney, he occasionally taught courses and seminars at the University of California Berkeley and San Francisco State University, and even returned to his hometown of El Paso as visiting Professor of Philosophy to teach aesthetics at the University of Texas. As part of the assigned coursework, he encouraged students to visit one another’s homes to get a sense of each individual’s aesthetic choices. “Everyone is an artist,” González says. “You can not be human without making art.”

He retired in 1998, in part because the increased illiteracy of his college-age students made his job harder though less challenging. “Grading became more of a chore; class sizes were larger.” Students were entering college without the rudimentary skills in reading and composition. He lays this problem at the doors of those who promoted and passed Proposition 13 (the 1978 tax revolt which massively reduced public school funding). As an instructor “there was less time to comment on logic and the development of an argument,” and an increased need to focus solely on punctuation and sentence structure. After leaving Laney, he occasionally taught courses and seminars at the University of California Berkeley and San Francisco State University, and even returned to his hometown of El Paso as visiting Professor of Philosophy to teach aesthetics at the University of Texas. As part of the assigned coursework, he encouraged students to visit one another’s homes to get a sense of each individual’s aesthetic choices. “Everyone is an artist,” González says. “You can not be human without making art.”

A citizen of U.S./Mexican border culture, with both parents having deep roots in Mexico (Durango and Torréon), González is completely at ease speaking and writing both English and Spanish. He writes poems simultaneously in Spanish and in English, but at one time, he felt he had to select the version that sounded the most 'authentic . . . "whatever that is," he jokes. Knowing that the two versions were really one poem, he decided that it was dishonest to separate them and call them two distinct poems, to deny that they were part of one another. He has never described what he does as translation. “I think of a line in Spanish, then in English or in English, then in Spanish.“ The poem comes about through an effortless move back and forth between the two vocabularies. Now, when he sends work for publication, he insists that both the Spanish and English version be printed as he has no interest in publishing what he considers to be a truncated poem.

González has spent less time on his publishing career than his politics and teaching. For years, he has shared poems on a monthly basis via email to friends and acquaintances fortunate enough to be on his list. His last book was published first in 1977: El hacedor de juegos (The Maker of Games) contained 54 poems and had a second edition in 1978. Since then, he has published poems in journals and magazines. A new collection of his work is in preparation now and scheduled for a late October release; it is La musa lunática (The Lunatic Muse) and is anxiously awaited by his readers.

González has spent less time on his publishing career than his politics and teaching. For years, he has shared poems on a monthly basis via email to friends and acquaintances fortunate enough to be on his list. His last book was published first in 1977: El hacedor de juegos (The Maker of Games) contained 54 poems and had a second edition in 1978. Since then, he has published poems in journals and magazines. A new collection of his work is in preparation now and scheduled for a late October release; it is La musa lunática (The Lunatic Muse) and is anxiously awaited by his readers.

The older he gets, says the 74-year-old poet, the more important he finds the matter of accessibility in the writing. “Poetry does not depend so much on the dazzling combination of words or metaphors but on the spirit of a relationship to Earth, to our wonder of it; poetry shouldn’t require a great vocabulary.” Poets who have inspired him include the ones his mother read long ago, such as García Lorca and Pablo Neruda, but also Walt Whitman, Dylan Thomas, Wallace Stevens and William Stafford. “Erudition should not interfere with accessibility,” he believes, and offers the advice to young writers to “give their Thesaurus to their worst friend.” Instead, he believes reading and conversing with other people who love literature is the best way to develop your working vocabulary.

In his work, art and politics segue completely. He speaks of the “old cosmology” as having reached its limit, and the need for basing our future on a reverence for the Earth. “If She is wounded, we are wounded.” In spite of the daily news, González insists he is still only “a pessimist of the intellect” but “an optimist of the heart.” In truth, he would “rather be writing love poems” than having to devote so much time to the issues of the day that concern him: global warming, alternative energy, the fight for universal healthcare, peace and justice issues. “My rantings and ravings are manifestations of a love outraged.” The public is invited to the City of Berkeley’s honoring of González.

Copyrighted photographs by Jannie M. Dresser.

-

-----------Chasco y Regalo

-----------Chasco y Regalo

.jpg)

.jpg)

Email

Email