Conocí a Frida por primera vez en el verano de 1950, tenía yo quince años de edad y en un viaje a México mi padre nos llevó a la familia al museo nacional de arte moderno. Allí conocí a Frida en doble, un lienzo grande (el más grande que creo jamás haya pintado) en que dos Fridas, una vestida de blanco en el estilo de fines del siglo XIX y la otra en traje tehuano, sentadas ante un cielo atormentado, se cogían de la mano, los corazones expuestos y sangrando, las miradas clavadas en la mía. Quedé absorto y fascinado. Mi madre tuvo que desprenderme jalándome de la mano.

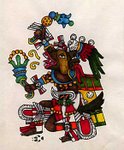

Creo que entonces me enamoré de Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo Calderón. La buscaba por dondequiera; entonces sus cuadros no eran tan fáciles de encontrar como los de su esposo Diego. Cuando los encontraba, allí estaba ella, siempre mirándome con mirada fija y estoica aunque en muchos de ellos el dolor que ostentaba como una flor maligna o un joya venenosa era palpable — collares de espinas; corsés como instrumentos de tortura medievales; la espina vertebral expuesta, una columna quebrada; una que otra lágrima como adorno de perla, gotas de sangre como alhajas de rubí. Cada uno de estos pequeños cuadros era como una reliquia preciosa del sufrir o una golosina de dolor, retablos como mandas por algún milagro perverso, exvotos a un dios cruel. Lo que me asombraba eran los colores, la sensualidad, la belleza con que celebraban su dolor. Entre los cincuenta y tanto autorretratos que pintó, aun en los que no aparecen imágenes del dolor, jamás, de que yo sepa, se pintó sonriente.

Poco a poco me enteré de su historia — su rebeldía precoz, el polio que de niña le atacó, el accidente de tranvía atroz que de joven la dejó en pedazos, su amor obsesivo por Diego (aunque no tan obsesivo que le impidiera otros amores con hombre o mujer), su valor que prestaba fuerza a su empeño por la alegría (que a veces ha de haber fingido), su culto a la vanidad, su afán por prendas regionales, joyas arqueológicas tan pesadas que le han de haber costado llevar, su alarde de mestiza.

Ahora la encuentro por dondequiera, aun en las películas, y en los bailes de disfraz parece que se multiplica cada vez más; la encuentro en las salas, los comedores, las cocinas, las recámaras, los baños. A veces me causa celos, mi Frida promiscua, ubicua.

© Rafael Jesús González 2010

I first knew Frida the summer of 1950; I was fifteen years old and on a trip to México my father took the family to the National Museum of Modern Art. There I met Frida in double, a large canvas (the largest one I believe she ever painted) in which two Fridas, one dressed in white in the style of the end of the 19th century and the other in the dress of Tehuantepec, seated before a tormented sky, held each others hand, their hearts exposed and bleeding, their gazes locked onto mine. I stood there absorbed and fascinated. My mother had to pull me away dragging me by the hand.

I believe it was then that I fell in love with Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo Calderón. I sought her everywhere; then, her paintings were not as easy to find as her husband Diego’s. Whenever I found them, there she was, always looking at me with fixed and stoic gaze even though in many of them the pain she displayed like a malignant flower or poisonous jewel, was palpable — necklaces of thorns; corsets like medieval instruments of torture; the exposed vertebral spine, a broken column; a few tears like pearl ornaments, drops of blood like ornaments of ruby. Each of these small paintings was like a precious reliquary of suffering, a delicacy of pain, offerings for some perverse miracle, ex votos to a cruel god. What amazed me were the colors, the sensuality, the beauty with which they celebrated her pain. Among the fifty some odd self-portraits, even in the ones in which there appear no images of pain, never, that I know of, did she paint herself smiling.

Little by little, I came to know her history — her precocious rebellion, the polio that attacked her as a child, the terrible trolley accident that left her in pieces young, her obsessive love of Diego (though not so obsessive that it prevented other loves with man or woman), her courage that lent strength to her determination for joy (which at times she must have feigned), her cult of vanity, her zeal for regional costumes, archaeological jewels so heavy that they must have hurt her to wear them, her boasts of being mestiza.

Now I find her everywhere, even in films, and at costume balls she seems to multiply herself more and more; I find her in the salons, the dining rooms, the kitchens, the bedrooms, the bathrooms. She sometimes makes me jealous, my promiscuous, ubiquitous Frida.

© Rafael Jesús González 2010

-

-

-

-

No comments:

Post a Comment