-

The Atom Bomb & I

In 1945 two months short of my turning ten, my mother celebrated her saint’s day, July 16 in Southwestern General Hospital, El Paso, Texas for some reason that I can’t remember. We visited her with flowers and she told of waking very early dawn to a brilliant glare out the window. Others also talked of the phenomenon. The next day, on page 6 of the El Paso Herold Post appeared a brief notice that a large arsenal in the army base of Alamo Gordo, New Mexico, not far away, had accidentally blown up.

Short of a month later, on August 6 the U.S. dropped the first atom bomb on Hiroshima, Japan. We had hardly news of the devastation when three days later another was dropped on Nagasaki.

The shock of the horror of it was covered by the air of festivity at the family gathering at our home shortly after to celebrate the defeat of Japan and the end of the Second World War; my uncles Tío Pana and Tío Kiki were coming home from the far Pacific and Europe.

But the war did not end; it just turned cold. The enemy was no longer fascist Germany, Italy, Japan, but a former ally, communist Russia. The atomic bomb was a threat hanging over the world. At school, the regular fire drills orderly vacating the building to the shrill buzzing of alarms were interspersed with “duck & cover” atomic-bombing drills that had us face away from the windows, cover our heads, and duck under our desks from which some times came contagious giggles that exasperated the teachers.

We became more and more aware of the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and fears (and hate of Russia) were stoked by the military-industrial complex that the post-war Republican president, a general, had warned us about. Private “bomb-shelters” were widely talked about and built in home backyards. In Junior High school, school mates of more well-to-do families talked about their fathers building “shelters,” their mothers stocking them with canned food. I came home from school one day and asked my father when we were going to build ours. He looked at me and asked: Do you know what an atomic bomb does? Would you want to live in a world destroyed by atom bombs? I was fifteen years old then. His question stuck with me ever since.

Many years of atomic war crises later, in 1983, teaching at Laney College, Oakland, California, I took leave of absence to help organize the First International Day of Nuclear Disarmament and take part in direct actions (civil disobedience) against nuclear weapons. A second-rate cowboy actor from California was president who dropped the mask of “defense” and turned to “first-strike” missiles and was set on taking the cold war to the stars. The beginning of that year, in Lompoc Federal Prison for trying to block the test of the MX missile, I wrote:

Here for Life

(Vandenberg Air Force Base, January 1983;

first blockade of MX Missile testing)

I am here —

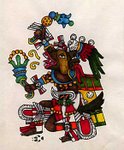

I wear the old-ones’ jade —

it’s life, they said & precious;

turquoise I’ve sought to hone my visions;

& coral to cultivate the heart;

mother of pearl for purity.

I have put on what power I could

to tell you there are mountains

where the stones sleep —

hawks nest there

& lichens older than the ice is cold.

The sea is vast & deep

keeping secrets

darker than the rocks are hard.

I am here to tell you

the Earth is made of things

so much themselves

they make the angels kneel.

We walk among them

& they are certain as the rain is wet

& they are fragile as the pine is tall.

We, too, belong to them;

they count upon our singing,

the footfalls of our dance,

our children’s shouts, their laughter.

I am here for the unfinished song,

the uncompleted dance,

the healing,

the dreadful fakes of love.

I am here for life

& I will not go away.

Rafael Jesús González

(Voices for Peace Anthology, Barbara Nestor Davis, Ed.;

Rochester, N.Y. 1983.

DNA ezine, Dragonfly Press, August 2020;

Author’s copyrights.)

It is 76 years since the first atom bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, the second one on Nagasaki. Again, we gather at the gates of Livermore Nuclear Laboratories in direct action to protest the production and proliferation of nuclear weapons that threaten the world even more. Now grown old, I am still here for life and for as long as I have the voice, I will raise it for the Earth, for justice without which there can be no peace, for Life.

Rafael Jesús González

Berkeley, California; August 6, 2021

Berkeley, California; August 6, 2021

La Bomba Atómica y Yo

En 1945 dos meses cortos de cumplir diez, mi madre celebró su día de santo el 16 de julio en el Hospital General Southwestern, El Paso, Texas por alguna razón que no recuerdo. La visitamos con flores y nos contó haber despertado muy temprano en la madrugada a un resplandor brillante por la ventana. Otros también hablaban del fenómeno. El día siguiente en la página 6 del diario El Paso Herold Post apareció una breve noticia que un arsenal grande en la base militar de Álamo Gordo, Nuevo México no lejos había estallado accidentalmente.

Corto de un mes después, el 6 de agosto los EE.UU. dejaron caer la primera bomba nuclear sobre Hiroshima, Japón. Apenas teníamos noticia de la calamidad cuando tres días después otra fue dejada caer en Nagasaki.

El choque del horror de esto se cubrió por el aire de festejo en la reunión familiar en nuestra casa poco después para celebrar el derrote de Japón y el fin de la Segunda Guerra Mundial; mis tíos, tío Pana y tío Kiki vendrían a casa del Pacífico lejano y de Europa.

Pero la guerra no acabó; solamente se volvió fría. El enemigo ya no era Alemania, Italia, Japón fascistas sino un ex aliado, Rusia comunista. La bomba atómica era amenaza sobre el mundo. En la escuela los simulacros de incendio regulares que ordenadamente vaciaban el edificio al estridente zumbar de las alarmas se intercalaban con simulacros de bombardeo atómico de “agacharse y taparse” que nos tenían de espaldas a las ventanas, taparnos la cabeza y agacharnos debajo de nuestros escritorios de los cuales a veces salían risitas contagiosas que exasperaban a las maestras.

Nos hicimos más y más conscientes de los horrores de Hiroshima y Nagasaki y temores (y odio a Rusia) se atizaban por el complejo miliar-industrial del que el presidente republicano de la posguerra, un general nos advertía. Se hablaba mucho de “refugios antiaéreos” privados y se construían detrás de las casas. En la escuela secundaria los compañeros de escuela de familias más acomodadas hablaban de sus padres construyendo “refugios” y sus madres llenándolos de comida en lata. Un día vine a casa y le pregunté a mi padre cuando íbamos a construir la nuestra. Me miró y me pregunto — ¿Sabes lo que hace una bomba atómica? ¿Quisieras vivir en un mundo destruido por bombas atómicas? Tenía yo quince años. Su pregunta se me quedó grabada desde entonces.

Muchos años de crisis de guerra atómica después, en 1983, enseñando en el Colegio Laney en Oakland, California, tomé permiso de ausencia para ayudar organizar el Primer Día Internacional del Desarme Nuclear y participar en acciones directas (desobediencia civil) contra las armas nucleares. Un actor de vaqueros de segunda clase era presidente que dejó la máscara de “defensa” y se volvió hacia misiles de “primer ataque” y estaba decido llevar la guerra fría a las estrellas. A principios de ese año, en la Prisión Federal de Lompoc por intentar bloquear la prueba del misil MX, escribí:

Aquí por vida

(Base de Fuerza Aérea de Vandenberg, enero 1983;

primer bloqueo de la prueba del proyectil nuclear MX)

Aquí estoy —

llevo el jade de los ancianos —

es la vida, decían, y preciosa;

turquesa que he buscado

para darles filo a mis visiones;

y coral para cultivar el corazón;

madreperla para la pureza.

Me he puesto el poder que pude

para decirles que hay montañas

donde duermen las piedras —

halcones anidan allí

y liquen más viejo

de lo que el hielo es frío.

El mar es vasto y profundo

guardando secretos

más oscuros

de lo que las rocas son duras.

Aquí estoy para decirles

que la Tierra es hecha de cosas

tan suyas mismas

que hacen a los ángeles arrodillarse.

Caminamos entre ellas

y son ciertas como la lluvia es húmeda

y son frágiles como el pino es alto.

Nosotros también les pertenecemos;

cuentan con nuestro cantar,

los pasos de nuestro bailar,

los gritos de nuestros hijos, su risa.

Aquí estoy por la canción no acabada,

el baile incompleto,

el sanar,

las terribles adujas del amor.

Aquí estoy por vida

y no me iré.

Rafael Jesús González

(DNA ezine, Dragonfly Press, agosto 2020;

derechos reservados del autor)

Hace 76 años que la primera bomba atómica se dejó caer en Hiroshima, la segunda en Nagasaki. Otra vez nos reunimos a la puertas de los Laboratorios Nucleares Livermore en acción directa para protestar contra la producción e incremento de las armas nucleares que amenazan aun más al mundo. Ya viejo, sigo aquí por vida y mientras tenga la voz, la alzaré por la Tierra, por la justicia sin la cual no puede haber paz, por la Vida.

Rafael Jesús González

Berkeley, California; 6 de agosto 2021

-

Berkeley, California; 6 de agosto 2021

-

No comments:

Post a Comment