-

-

---Solsticio invernal

Y cuando es la oscuridad

confiamos en los dioses

que la luz sea —

pero aun

tendremos que cantar

la luz a ser.

------© Rafael Jesús González 2008

------Winter Solstice

And when the darkness is,

we trust upon the gods

that light might be —

but still

we must sing

the light into being.

-----© Rafael Jesús González 2008

-

-

Sunday, December 21, 2008

Monday, December 15, 2008

Bouquet of the season

--

-

In the cold whiteness,

scalloped green flags, red lanterns —

holly in the snow —

more festive, more lovely than

tinsel strung across the streets.

Mistletoe Tanka

Mistletoe Tanka

Winter stripped the trees,

but, they still greenly sport leaves,

fruiting mistletoe.

In scarce winter, the birds feast

and beneath it, fairies kiss.

-

Blessings of the season in which the Winter Solstice

brings increase of light;

may it illuminate our hearts & minds

that we may heal, achieve justice, find peace

& realize the paradise

from which we have never been expelled.

brings increase of light;

may it illuminate our hearts & minds

that we may heal, achieve justice, find peace

& realize the paradise

from which we have never been expelled.

In the cold whiteness,

scalloped green flags, red lanterns —

holly in the snow —

more festive, more lovely than

tinsel strung across the streets.

--------------------------------------------©Rafael Jesús González 2008

Mistletoe Tanka

Mistletoe TankaWinter stripped the trees,

but, they still greenly sport leaves,

fruiting mistletoe.

In scarce winter, the birds feast

and beneath it, fairies kiss.

© Rafael Jesús González 2008

Flor de Noche Buena Tanka

Because it blooms at

midwinter’s holiest dark,

the friars called it

Flor de la Noche Buena,

bloom of the light-birthing night.

-

Because it blooms at

midwinter’s holiest dark,

the friars called it

Flor de la Noche Buena,

bloom of the light-birthing night.

-----------------------------------------© Rafael Jesús González 2008

--

Friday, December 12, 2008

Full Moon of Winter

-

---Luna plena de invierno

La luna plena de invierno

canta con voz de oboe

en contrapunto al pizzicato

de las estrellas.

Es una fuga brillante y fría

que llena la cúpula oscura

de plata y melancolía.

---© Rafael Jesús González 2008

---- Full Moon of Winter

The full moon of winter

sings with the voice of the oboe

in counterpoint to the pizzicato

of the stars.

It is a bright & cold fugue

that fills the dark dome

with silver & melancholy.

-----© Rafael Jesús González 2008

-

---Luna plena de invierno

La luna plena de invierno

canta con voz de oboe

en contrapunto al pizzicato

de las estrellas.

Es una fuga brillante y fría

que llena la cúpula oscura

de plata y melancolía.

---© Rafael Jesús González 2008

---- Full Moon of Winter

The full moon of winter

sings with the voice of the oboe

in counterpoint to the pizzicato

of the stars.

It is a bright & cold fugue

that fills the dark dome

with silver & melancholy.

-----© Rafael Jesús González 2008

-

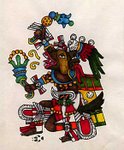

Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe

-

-

------Rezo a Tonantzin

Tonantzin

---madre de todo

---lo que de ti vive,

es, habita, mora, está;

Madre de todos los dioses

------------------las diosas

madre de todos nosotros,

-------la nube y el mar

-------la arena y el monte

-------el musgo y el árbol

-------el ácaro y la ballena.

Derramando flores

haz de mi manto un recuerdo

que jamás olvidemos que tú eres

único paraíso de nuestro vivir.

Bendita eres,

cuna de la vida, fosa de la muerte,

fuente del deleite, piedra del sufrir.

concédenos, madre, justicia,

--------concédenos, madre, la paz.

---------© Rafael Jesús González 2007

----Prayer to Tonantzin

Tonantzin

-----mother of all

-----that of you lives,

be, dwells, inhabits, is;

Mother of all the gods

---------------the goddesses

Mother of us all,

---------the cloud & the sea

---------the sand & the mountain

---------the moss & the tree

---------the mite & the whale.

Spilling flowers

make of my cloak a reminder

that we never forget that you are

the only paradise of our living.

Blessed are you,

cradle of life, grave of death,

fount of delight, rock of pain.

Grant us, mother, justice,

-------grant us, mother, peace.

--------© Rafael Jesús González 2007

-

-

-

------Rezo a Tonantzin

Tonantzin

---madre de todo

---lo que de ti vive,

es, habita, mora, está;

Madre de todos los dioses

------------------las diosas

madre de todos nosotros,

-------la nube y el mar

-------la arena y el monte

-------el musgo y el árbol

-------el ácaro y la ballena.

Derramando flores

haz de mi manto un recuerdo

que jamás olvidemos que tú eres

único paraíso de nuestro vivir.

Bendita eres,

cuna de la vida, fosa de la muerte,

fuente del deleite, piedra del sufrir.

concédenos, madre, justicia,

--------concédenos, madre, la paz.

---------© Rafael Jesús González 2007

----Prayer to Tonantzin

Tonantzin

-----mother of all

-----that of you lives,

be, dwells, inhabits, is;

Mother of all the gods

---------------the goddesses

Mother of us all,

---------the cloud & the sea

---------the sand & the mountain

---------the moss & the tree

---------the mite & the whale.

Spilling flowers

make of my cloak a reminder

that we never forget that you are

the only paradise of our living.

Blessed are you,

cradle of life, grave of death,

fount of delight, rock of pain.

Grant us, mother, justice,

-------grant us, mother, peace.

--------© Rafael Jesús González 2007

-

-

Thursday, November 27, 2008

Thanksgiving

-

-

-----------------Grace

Thanks & blessing be

to the Sun & the Earth

for this bread & this wine,

----this fruit, this meat, this salt,

---------------this food;

thanks be & blessing to them

who prepare it, who serve it;

thanks & blessing to them

who share it

-----(& also the absent & the dead.)

Thanks & blessing to them who bring it

--------(may they not want),

to them who plant & tend it,

harvest & gather it

--------(may they not want);

thanks & blessing to them who work

--------& blessing to them who cannot;

may they not want — for their hunger

------sours the wine

----------& robs the salt of its taste.

Thanks be for the sustenance & strength

for our dance & the work of justice, of peace.

----------------------© Rafael Jesús González 2008

(The Montserrat Review, Issue 6, Spring 2003

[nominated for the Hobblestock Peace Poetry Award];

author’s copyrights.)

-------------Gracias

Gracias y benditos sean

el Sol y la Tierra

por este pan y este vino,

-----esta fruta, esta carne, esta sal,

----------------este alimento;

gracias y bendiciones

a quienes lo preparan, lo sirven;

gracias y bendiciones

a quienes lo comparten

(y también a los ausentes y a los difuntos.)

Gracias y bendiciones a quienes lo traen

--------(que no les falte),

a quienes lo siembran y cultivan,

lo cosechan y lo recogen

-------(que no les falte);

gracias y bendiciones a los que trabajan

-------y bendiciones a los que no puedan;

que no les falte — su hambre

-----hace agrio el vino

-----------y le roba el gusto a la sal.

Gracias por el sustento y la fuerza

para nuestro bailar y nuestra labor

--------por la justicia y la paz.

---------------© Rafael Jesús González 2008

(The Montserrat Review, no. 6, primavera 2003

[nombrado para el Premio de la Poesía por la Paz Hobblestock;

derechos reservados del autor.)

-

-

---- -

-

-----------------Grace

Thanks & blessing be

to the Sun & the Earth

for this bread & this wine,

----this fruit, this meat, this salt,

---------------this food;

thanks be & blessing to them

who prepare it, who serve it;

thanks & blessing to them

who share it

-----(& also the absent & the dead.)

Thanks & blessing to them who bring it

--------(may they not want),

to them who plant & tend it,

harvest & gather it

--------(may they not want);

thanks & blessing to them who work

--------& blessing to them who cannot;

may they not want — for their hunger

------sours the wine

----------& robs the salt of its taste.

Thanks be for the sustenance & strength

for our dance & the work of justice, of peace.

----------------------© Rafael Jesús González 2008

(The Montserrat Review, Issue 6, Spring 2003

[nominated for the Hobblestock Peace Poetry Award];

author’s copyrights.)

[reading and commentary http://www.blogtalkradio.com/wandas-picks

for November 26, 2008]

for November 26, 2008]

-------------Gracias

Gracias y benditos sean

el Sol y la Tierra

por este pan y este vino,

-----esta fruta, esta carne, esta sal,

----------------este alimento;

gracias y bendiciones

a quienes lo preparan, lo sirven;

gracias y bendiciones

a quienes lo comparten

(y también a los ausentes y a los difuntos.)

Gracias y bendiciones a quienes lo traen

--------(que no les falte),

a quienes lo siembran y cultivan,

lo cosechan y lo recogen

-------(que no les falte);

gracias y bendiciones a los que trabajan

-------y bendiciones a los que no puedan;

que no les falte — su hambre

-----hace agrio el vino

-----------y le roba el gusto a la sal.

Gracias por el sustento y la fuerza

para nuestro bailar y nuestra labor

--------por la justicia y la paz.

---------------© Rafael Jesús González 2008

(The Montserrat Review, no. 6, primavera 2003

[nombrado para el Premio de la Poesía por la Paz Hobblestock;

derechos reservados del autor.)

[lectura y comentario http://www.blogtalkradio.com/wandas-picks

del 26 noviembre 2008]

del 26 noviembre 2008]

-

----- -

Thursday, November 13, 2008

Full moon: Moon for Obama

-

“— the White House of future poems,” wrote the good gray poet, “and of dreams and dramas, there in the soft and copious moon—.” And he sang of the vistas of Democracy in these United States and perhaps dreamt (he did not say) that one day this house he praised, built in great part by slaves from Africa, would be home to a man and his family of African descent much, much more recent than that of most of us.

For a bad long while the vision the poet sang turned nightmare, a fearful tale from the Arabian nights, the singer, lover of Lincoln, at risk of losing his head at the tale’s end, the White House fenced in and barricaded, Democracy but a sham, an empty shibboleth, profane password into the prison cell, or worse, the torture chamber, the Constitution shredded and our freedoms raped.

Tonight the soft and copious moon promises that those pale and livid walls of power will at last have some color and that Democracy is not yet dead, that our blood still flows red and rich with joy and hope of change, the love of freedom and desire for justice strong in our good will.

The moon watches, as does the world, for a turn of things, for the ray of light to blaze into full day, not an immediate paradise, but of an Earth healed, a humanity more free, more just, more peaceful, more compassionate, more hopeful, and more full of joy.

The world watches and so does godmother moon, soft and copious.

“— la Casa Blanca de poemas futuros,” escribió el buen poeta pardo, “y de sueños y dramas, allí en la suave y copiosa luna —.” Y cantó de las vistas de la Democracia en estos Estados Unidos y tal vez soñó (no dijo) que algún día esta casa que elogiaba, construida en gran parte por esclavos de África, sería hogar para un hombre y su familia de descendencia africana mucho, mucho más reciente que la nuestra de la gran parte de nosotros.

Por un mal y largo tiempo la visión que el poeta cantaba se volvió pesadilla, un cuento espantoso de las noches árabes, el cantor, amante de Lincoln, a riesgo de perder la cabeza al fin de la narrativa, la Casa Blanca cercada y barreada, la Democracia sino una farsa, un mote vacío, una contraseña a la celda de prisión, o peor, a la sala de tortura, la Constitución hecha garras y nuestras libertades violadas.

Esta noche la luna suave y copiosa promete que estos muros del poder pálidos y lívidos al fin tengan algo de color y que la democracia no está ya muerta, que nuestra sangre aun fluye roja y rica con regocijo y esperanza de cambio, el amor por la libertad y el deseo por la justicia fuertes en nuestra buena voluntad.

La luna está en mire, tal como el mundo, de un cambio de cosas, que el rayo de luz encienda en día pleno, no un paraíso inmediato, sino una Tierra sanada, una humanidad más libre, más justa, más apacible, más compasiva, de más esperanza, y de más alegría.

El mundo espera y también madrina luna, suave y copiosa.

Moon for Obama

“— the White House of future poems,” wrote the good gray poet, “and of dreams and dramas, there in the soft and copious moon—.” And he sang of the vistas of Democracy in these United States and perhaps dreamt (he did not say) that one day this house he praised, built in great part by slaves from Africa, would be home to a man and his family of African descent much, much more recent than that of most of us.

For a bad long while the vision the poet sang turned nightmare, a fearful tale from the Arabian nights, the singer, lover of Lincoln, at risk of losing his head at the tale’s end, the White House fenced in and barricaded, Democracy but a sham, an empty shibboleth, profane password into the prison cell, or worse, the torture chamber, the Constitution shredded and our freedoms raped.

Tonight the soft and copious moon promises that those pale and livid walls of power will at last have some color and that Democracy is not yet dead, that our blood still flows red and rich with joy and hope of change, the love of freedom and desire for justice strong in our good will.

The moon watches, as does the world, for a turn of things, for the ray of light to blaze into full day, not an immediate paradise, but of an Earth healed, a humanity more free, more just, more peaceful, more compassionate, more hopeful, and more full of joy.

The world watches and so does godmother moon, soft and copious.

© Rafael Jesús González 2008

-

Luna para Obama

Luna para Obama

“— la Casa Blanca de poemas futuros,” escribió el buen poeta pardo, “y de sueños y dramas, allí en la suave y copiosa luna —.” Y cantó de las vistas de la Democracia en estos Estados Unidos y tal vez soñó (no dijo) que algún día esta casa que elogiaba, construida en gran parte por esclavos de África, sería hogar para un hombre y su familia de descendencia africana mucho, mucho más reciente que la nuestra de la gran parte de nosotros.

Por un mal y largo tiempo la visión que el poeta cantaba se volvió pesadilla, un cuento espantoso de las noches árabes, el cantor, amante de Lincoln, a riesgo de perder la cabeza al fin de la narrativa, la Casa Blanca cercada y barreada, la Democracia sino una farsa, un mote vacío, una contraseña a la celda de prisión, o peor, a la sala de tortura, la Constitución hecha garras y nuestras libertades violadas.

Esta noche la luna suave y copiosa promete que estos muros del poder pálidos y lívidos al fin tengan algo de color y que la democracia no está ya muerta, que nuestra sangre aun fluye roja y rica con regocijo y esperanza de cambio, el amor por la libertad y el deseo por la justicia fuertes en nuestra buena voluntad.

La luna está en mire, tal como el mundo, de un cambio de cosas, que el rayo de luz encienda en día pleno, no un paraíso inmediato, sino una Tierra sanada, una humanidad más libre, más justa, más apacible, más compasiva, de más esperanza, y de más alegría.

El mundo espera y también madrina luna, suave y copiosa.

Tuesday, November 11, 2008

invitation to a reading in Berkeley

-

You are invited to

THE MUSIC OF THE WORD - LA PALABRA MUSICAL

hosted by Avotcja & Eric Aviles

featuring

Rafael Jesús González

&

Karla Brundage

Sunday November 23, 2008

3:30 PM

REBECCA's BOOKS

3268 Adeline Street

(½ block north of Alcatraz,

2 short blocks south of Ashby BART)

Berkeley, California

(510) 852 - 4768

rebeccasbooks@yahoo.com or www.Avotcja.com

ericaviles@yahoo.com or laverdadmusical@yahoo.com

“Let the music of your heart enhance the freedom that you seek”

-

THE MUSIC OF THE WORD - LA PALABRA MUSICAL

hosted by Avotcja & Eric Aviles

featuring

Rafael Jesús González

&

Karla Brundage

Sunday November 23, 2008

3:30 PM

REBECCA's BOOKS

3268 Adeline Street

(½ block north of Alcatraz,

2 short blocks south of Ashby BART)

Berkeley, California

(510) 852 - 4768

rebeccasbooks@yahoo.com or www.Avotcja.com

ericaviles@yahoo.com or laverdadmusical@yahoo.com

“Let the music of your heart enhance the freedom that you seek”

Veterans' Day

-

-

When the First World War officially ended June 28, 1919, the actual fighting had already stopped the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month the previous year. Armistice Day, as it was known, later became a national holiday, and in 1954 (the year I graduated from high school), the name was changed to Veterans Day to honor all U.S. veterans of all wars.

The only veteran of that war, “the war to end all wars”, I ever knew was my father’s step-father Benjamín Armijo, from New Mexico, an old man who seldom spoke and whom I would on occasion see wearing his cap of The American Legion. (He was also Republican.)

“The war to end all wars” was anything but that and when I was not much more than five, three of my uncles on my mother’s side (Roberto, Armando, Enrique) went off to fight another war, the Second World War.

“The war to end all wars” was anything but that and when I was not much more than five, three of my uncles on my mother’s side (Roberto, Armando, Enrique) went off to fight another war, the Second World War.

I missed my uncles and remembered them by their photos on my grandmother’s home altar, very handsome in their uniforms; in the endless rosaries and litanies the women in the family regularly met to pray; and in the three blue stars that hanged in the window.

My uncle Roberto, tío Beto, did not last his second year; he came home and ulcers and los nervios, nerves, were mentioned. My uncle Armando, tío Pana, in the Infantry division or the Cavalry Division (though not one horse was ever ridden into battle in that war), served in the Pacific Theater, and Guadalcanal is a name that in some way sticks in his history. My uncle Enrique, tío Kiki, the youngest, in the Airborne Division, the “Screaming Eagles,” served in the European Theater and parachuted into the taking of Germany.

After that war ended, they came home, tío Pana into a hospital, sick with malaria which affected him throughout the rest of his life; tío Kiki with a malady in the soul not so easily diagnosed, hidden in his quiet humor, gentle ways. All my uncles were gentle men, in all senses of the word. And Beto, Pana, Kiki spoke not at all about their experiences of war in spite of my curiosity and questions which they diverted with a little joke or change of subject. What they had seen, felt was apparently not to be spoken and the family sensed this and respected their reticence. Neither of them joined the Veterans of Foreign Wars that I ever knew.

The Korean War “broke out”, as they say, as if it were acne, not long after. But as for me, I have never fought in any war, though I joined the U. S. Navy upon graduating from El Paso High School to become a Hospital Corpsman and obtain the G.I. Bill with which to enter Pre-Med studies upon my discharge; two of four years in the Navy I spent in the Marine Corps with the rank of Staff Sergeant. The Korean War had already ended. And though I served closely enough to it to be given the Korea Defense Service Medal and am legally a veteran and eligible to join the VFW, I never did nor do I intend to.

If I consider myself veteran of any war, it would be of the Viet-Nam War, not because I fought in it, far from it, but because I struggled against it. (I counseled conscientious objectors, picketed recruiting offices, marched in the streets.) The war veterans I have most intimately known are from that war, many, if not most, wounded and ill in body (from bullets, shrapnel, agent-orange), wounded and ill in the soul (terror, guilt, shame, hatred putrefying their dreams, tainting their loves.)

I am leery of being asked to honor veterans of almost any war, except as I honor the suffering, the being of every man or woman who ever lived. I am sick of “patriotism” behind which so many scoundrels hide. I am sick of war that has stained almost every year of my life. Especially now, in the midst of yet another unjustified, immoral, illegal, untenable, cynical, cruel war our nation wages in Iraq. I am impatient with fools who ask whether I “support our troops.”

What does it mean to “support our troops”? What is a troop but a herd, a flock, a band? What is a troop but a group of actors whose duty it is not to reason why, but to do and die? In the years I served in the Navy and Marine Corps as a medic, I never took care of a troop; I took care of men who had been wounded and hurt, who cut themselves and bled, who suffered terrible blisters on their feet from long marches, who fell ill sick with high fevers. If to support means to carry the weight of, keep from falling, slipping, or sinking, give courage, faith, help, comfort, strengthen, provide for, bear, endure, tolerate, yes, I did, and do support all men and women unfortunate enough to go to war.

Troops, I do not. If to support means to give approval to, be in favor of, subscribe to, sanction, uphold, then I do not. The decision to make war was/is not theirs to make; troops are what those who make the decisions to war use (to kill and to be killed, to be brutalized into torturers) for their own ends, not for the sake of the men and woman who constitute the “troops.”

I honor veterans of war the only way in which I know how to honor: with compassion; with respect; with understanding for how they were/are used, misled, indoctrinated, coerced, wasted, hurt, abandoned; with tolerance for their beliefs and justifications; with efforts to see that their wounds, of body and of soul, are treated and healed, their suffering and sacrifice compensated. I never refuse requests for donations to any veterans’ organization that seeks benefits and services for veterans. I honor veterans, men and woman; not bands, not troops.

If you look to my window on this day, the flag you will see hanging there will be the rainbow flag of peace. It hangs there in honor of every veteran of any war of any time or place. Indoors, I will light a candle and burn sage, recommit myself to the struggle for justice and for peace. Such is the only way I know in which to honor the veterans of war, military or civilian.

-

-Veterans Day

When the First World War officially ended June 28, 1919, the actual fighting had already stopped the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month the previous year. Armistice Day, as it was known, later became a national holiday, and in 1954 (the year I graduated from high school), the name was changed to Veterans Day to honor all U.S. veterans of all wars.

The only veteran of that war, “the war to end all wars”, I ever knew was my father’s step-father Benjamín Armijo, from New Mexico, an old man who seldom spoke and whom I would on occasion see wearing his cap of The American Legion. (He was also Republican.)

“The war to end all wars” was anything but that and when I was not much more than five, three of my uncles on my mother’s side (Roberto, Armando, Enrique) went off to fight another war, the Second World War.

“The war to end all wars” was anything but that and when I was not much more than five, three of my uncles on my mother’s side (Roberto, Armando, Enrique) went off to fight another war, the Second World War.I missed my uncles and remembered them by their photos on my grandmother’s home altar, very handsome in their uniforms; in the endless rosaries and litanies the women in the family regularly met to pray; and in the three blue stars that hanged in the window.

My uncle Roberto, tío Beto, did not last his second year; he came home and ulcers and los nervios, nerves, were mentioned. My uncle Armando, tío Pana, in the Infantry division or the Cavalry Division (though not one horse was ever ridden into battle in that war), served in the Pacific Theater, and Guadalcanal is a name that in some way sticks in his history. My uncle Enrique, tío Kiki, the youngest, in the Airborne Division, the “Screaming Eagles,” served in the European Theater and parachuted into the taking of Germany.

After that war ended, they came home, tío Pana into a hospital, sick with malaria which affected him throughout the rest of his life; tío Kiki with a malady in the soul not so easily diagnosed, hidden in his quiet humor, gentle ways. All my uncles were gentle men, in all senses of the word. And Beto, Pana, Kiki spoke not at all about their experiences of war in spite of my curiosity and questions which they diverted with a little joke or change of subject. What they had seen, felt was apparently not to be spoken and the family sensed this and respected their reticence. Neither of them joined the Veterans of Foreign Wars that I ever knew.

The Korean War “broke out”, as they say, as if it were acne, not long after. But as for me, I have never fought in any war, though I joined the U. S. Navy upon graduating from El Paso High School to become a Hospital Corpsman and obtain the G.I. Bill with which to enter Pre-Med studies upon my discharge; two of four years in the Navy I spent in the Marine Corps with the rank of Staff Sergeant. The Korean War had already ended. And though I served closely enough to it to be given the Korea Defense Service Medal and am legally a veteran and eligible to join the VFW, I never did nor do I intend to.

If I consider myself veteran of any war, it would be of the Viet-Nam War, not because I fought in it, far from it, but because I struggled against it. (I counseled conscientious objectors, picketed recruiting offices, marched in the streets.) The war veterans I have most intimately known are from that war, many, if not most, wounded and ill in body (from bullets, shrapnel, agent-orange), wounded and ill in the soul (terror, guilt, shame, hatred putrefying their dreams, tainting their loves.)

I am leery of being asked to honor veterans of almost any war, except as I honor the suffering, the being of every man or woman who ever lived. I am sick of “patriotism” behind which so many scoundrels hide. I am sick of war that has stained almost every year of my life. Especially now, in the midst of yet another unjustified, immoral, illegal, untenable, cynical, cruel war our nation wages in Iraq. I am impatient with fools who ask whether I “support our troops.”

What does it mean to “support our troops”? What is a troop but a herd, a flock, a band? What is a troop but a group of actors whose duty it is not to reason why, but to do and die? In the years I served in the Navy and Marine Corps as a medic, I never took care of a troop; I took care of men who had been wounded and hurt, who cut themselves and bled, who suffered terrible blisters on their feet from long marches, who fell ill sick with high fevers. If to support means to carry the weight of, keep from falling, slipping, or sinking, give courage, faith, help, comfort, strengthen, provide for, bear, endure, tolerate, yes, I did, and do support all men and women unfortunate enough to go to war.

Troops, I do not. If to support means to give approval to, be in favor of, subscribe to, sanction, uphold, then I do not. The decision to make war was/is not theirs to make; troops are what those who make the decisions to war use (to kill and to be killed, to be brutalized into torturers) for their own ends, not for the sake of the men and woman who constitute the “troops.”

I honor veterans of war the only way in which I know how to honor: with compassion; with respect; with understanding for how they were/are used, misled, indoctrinated, coerced, wasted, hurt, abandoned; with tolerance for their beliefs and justifications; with efforts to see that their wounds, of body and of soul, are treated and healed, their suffering and sacrifice compensated. I never refuse requests for donations to any veterans’ organization that seeks benefits and services for veterans. I honor veterans, men and woman; not bands, not troops.

If you look to my window on this day, the flag you will see hanging there will be the rainbow flag of peace. It hangs there in honor of every veteran of any war of any time or place. Indoors, I will light a candle and burn sage, recommit myself to the struggle for justice and for peace. Such is the only way I know in which to honor the veterans of war, military or civilian.

Berkeley, November 11, 2007

© Rafael Jesús González 2008

Tuesday, November 4, 2008

Election of Senator Barack Obama, 44th President of the United States of America

-

Tonight Senator Barack Obama was elected the 44th president of the United States of America. I have often said that this election was the United States’ moment of truth. I am proud to say that we have faced that moment and we have done so honorably and have not been found wanting.

This is the only presidential election at which I have ever wept. Our country, empire that it is, that it has always been, has shown itself capable of change, of becoming more just, of overcoming its shameful legacy of racism enough to elect a man of undeniable African ancestry to the highest office of the land. That I have lived to see it gives me more joy, more hope than I can say.

As for Senator Obama the man, of his many virtues, I will not speak but only say that it makes my heart glad that he can smile; in eight long years, one can become very sick of a smirk. In his election speech he had the grace to place his election in its historical context and took the moment, not to aggrandize himself, but to place the responsibility for the welfare of the nation in our own hands, us the citizens, where, in a democracy, it truly must rest.

Senator Obama’s election as president of the nation is, more than a victory, a challenge and an opportunity for us as a people to truly begin to make of our country the democracy to which we have for so long pretended. The task will be difficult and long, but hope and faith has been renewed and change for the good is possible, nay, is imperative. Yes, we can. If we will.

Esta noche el senador Barack Obama fue elegido el cuarenta-cuarto presidente de los Estados Unidos de América. A menudo he dicho que estas elecciones eran el momento de la verdad para los Estados Unidos. Diré con orgullo que nos hemos enfrentado a ese momento y lo hemos hecho honorablemente y nos hemos encontrado capaces.

Esta es la única elección presidencial en la cual jamás he llorado. Nuestra nación, emperio que es, que siempre ha sido, se ha mostrado capaz de cambiar, de hacerse más justa, de superar su legado penoso de racismo lo suficiente como para elegir a un hombre de descendencia Africana innegable a la oficina más alta de la nación. Que he vivido para verlo me ocasiona más regocijo, más esperanza que de lo que pueda expresar.

En tanto al Senador Obama el hombre, de sus muchas virtudes no hablaré mas solamente para decir que me llena de alegría el corazón que él sea capaz de sonreír; en ocho largos años uno se puede hartar de la mueca complacida. En su discurso de elección tuvo la gracia de ubicar su elección dentro el marco histórico y tomó el momento, no para exaltarse a si mismo, sino para poner la responsabilidad por el bienestar de la nación en nuestras propias manos, nuestras de los ciudadanos, donde, en una democracia, verdaderamente debe estar.

La elección del senador Obama como presidente de la nación es, más que victoria, un reto y una oportunidad para nosotros como pueblo para verdaderamente empezar a hace de nuestro país la democracia a la cual hemos pretendido por hace tanto. La tarea será difícil y larga pero la esperanza y la fe se han renovado y el cambio para lo bueno es posible, no, imprescindible. Sí se puede. Si lo deseamos.

Tonight Senator Barack Obama was elected the 44th president of the United States of America. I have often said that this election was the United States’ moment of truth. I am proud to say that we have faced that moment and we have done so honorably and have not been found wanting.

This is the only presidential election at which I have ever wept. Our country, empire that it is, that it has always been, has shown itself capable of change, of becoming more just, of overcoming its shameful legacy of racism enough to elect a man of undeniable African ancestry to the highest office of the land. That I have lived to see it gives me more joy, more hope than I can say.

As for Senator Obama the man, of his many virtues, I will not speak but only say that it makes my heart glad that he can smile; in eight long years, one can become very sick of a smirk. In his election speech he had the grace to place his election in its historical context and took the moment, not to aggrandize himself, but to place the responsibility for the welfare of the nation in our own hands, us the citizens, where, in a democracy, it truly must rest.

Senator Obama’s election as president of the nation is, more than a victory, a challenge and an opportunity for us as a people to truly begin to make of our country the democracy to which we have for so long pretended. The task will be difficult and long, but hope and faith has been renewed and change for the good is possible, nay, is imperative. Yes, we can. If we will.

Rafael Jesús González

Esta noche el senador Barack Obama fue elegido el cuarenta-cuarto presidente de los Estados Unidos de América. A menudo he dicho que estas elecciones eran el momento de la verdad para los Estados Unidos. Diré con orgullo que nos hemos enfrentado a ese momento y lo hemos hecho honorablemente y nos hemos encontrado capaces.

Esta es la única elección presidencial en la cual jamás he llorado. Nuestra nación, emperio que es, que siempre ha sido, se ha mostrado capaz de cambiar, de hacerse más justa, de superar su legado penoso de racismo lo suficiente como para elegir a un hombre de descendencia Africana innegable a la oficina más alta de la nación. Que he vivido para verlo me ocasiona más regocijo, más esperanza que de lo que pueda expresar.

En tanto al Senador Obama el hombre, de sus muchas virtudes no hablaré mas solamente para decir que me llena de alegría el corazón que él sea capaz de sonreír; en ocho largos años uno se puede hartar de la mueca complacida. En su discurso de elección tuvo la gracia de ubicar su elección dentro el marco histórico y tomó el momento, no para exaltarse a si mismo, sino para poner la responsabilidad por el bienestar de la nación en nuestras propias manos, nuestras de los ciudadanos, donde, en una democracia, verdaderamente debe estar.

La elección del senador Obama como presidente de la nación es, más que victoria, un reto y una oportunidad para nosotros como pueblo para verdaderamente empezar a hace de nuestro país la democracia a la cual hemos pretendido por hace tanto. La tarea será difícil y larga pero la esperanza y la fe se han renovado y el cambio para lo bueno es posible, no, imprescindible. Sí se puede. Si lo deseamos.

Rafael Jesús González

-

Sunday, November 2, 2008

Feast of All Souls (Day of the Dead)

--

--

--Consejo para el peregrino a Mictlan

--Consejo para el peregrino a Mictlan

------------------------(al modo Nahua)

Cruza el campo amarillo de cempoales,

baja al reino de las sombras;

es amplio, es estrecho.

Interroga a los ancianos;

son sabios, son necios:

— Señores míos, Señoras mías,

¿Qué verdad dicen sus flores, sus cantos?

¿Son verdaderamente bellas, ricas sus plumas?

¿No es el oro sólo excremento de los dioses?

Sus jades, ¿son los más finos, los más verdes?

Su legado, ¿es tinta negra, tinta roja? —

Acepta sólo lo preciso:

-----lo que te haga amplio el corazón

--------lo que te ilumine el rostro.

------------------------© Rafael Jesús González 2007

-----Advice for the Pilgrim to Mictlan

------------------- (in the Nahua mode)

Cross the yellow fields of marigolds,

descend to the realm of shadows;

it is wide, it is narrow.

Question the ancients;

they are wise, they are fools:

— My Lords, My Ladies,

What truth do your flowers, your songs tell?

Are your feathers truly lovely, truly rich?

Is not gold only the excrement of the gods?

Your jades, are they the finest, the most green?

Your legacy, is it black ink, red ink? —

Accept only the necessary:

-----what will widen your heart

----what will enlighten your face.

------------------------© Rafael Jesús González 2007

[Descent to Mictlan, Land of the Dead: Trance Poem in the Nahua mode (commissioned by the Oakland Museum of California while the author was Poet in Residence under a Writers on Site award by Poets & Writers, Inc. and a grant from The James Irvine Foundation in 1996) was written as a performance piece for voice, drums, didgeridoos, and movement intended to guide the audience upon an introspective journey of the imagination down into the kingdom of Death.

It is not so much entertainment as it is ritual art which, with the consent of each person in the audience to give himself or herself to their imagination, would induce the heightened perception of trance to descend into our collective and personal past to examine the legacy of our ancestors. What they have given us, we have become. It may be read by the attentive reader in the same way.

The times demand that we take stock of who we are, for our great Mother the Earth is wounded and, to heal her, we must heal ourselves, learn from the wisdom of our forebears and discard their mistakes. And in return for what each brings back from the store house of the past, each must make a commitment, in good faith, to change and to heal ourselves; and to care for and protect the Earth, all that she bears, and each other in brotherhood and sisterhood of the spirit and of the flesh. It is a gift and a blessing. Any less and we risk our own extinction on the Earth.]

Cruzad el campo amarillo de cempoales.

Cross the yellow fields of marigolds.

Bajad al reino de las sombras — es amplio, es estrecho.

Descend to the realm of shadows — it is wide, it is narrow.

We come to the mouth of the cavern of caverns,

realm of Mictlantecuhtli, Mictlancihuatl,

Señor-Señora Muerte, Our Lord, Our Lady of Death —

It is wide, it is narrow;

pasad, enter this chamber of yellow blooms,

--------the cempoalxochitl, the shield flower,

------------flor de muertos, flower of the Dead.

We step, we walk;

-----we walk the sacred;

---------every step is sacred.

We walk in the tracks of our ancestors,

we step in the tracks of the old ones,

----our grandmothers, our grandfathers,

----the ancients:

--------the people of the drum

--------the people of the canoe

--------the people of the pyramids

--------the people of the spear

--------the people of the shuttle and loom

--------the people of the sickle and plow,

------------our ancient ones, all of the clans.

They taught us to see;

they taught us not to see;

-----from them we learned to see;

-----------we learned not to see.

They taught us to dream;

------they taught us to fear;

-----------much to learn, much to unlearn.

We step in their tracks, we step on the sacred.

We walk, we step in the tracks of our ancestors,

----our relations:

---------the ocelot

---------the buffalo

---------the coyote

---------the bear

---------the salmon, the serpent, the eagle, the hawk,

---------monkey, turtle, frog,

---------the owl and the bat.

Further, further we walk:

the spider, the moth, the fly, the coral, the mite,

ameba, paramecium, germ, virus - all of the clans.

They taught us to see, to live in the now,

------to smell, to taste,

------to hear, to live in the now.

We step in their tracks,

-----we walk on the sacred —

---------all our relations, all of the clans.

We walk, we step in the tracks of our ancestors,

our relations:

-----the fern, the redwood

-----the pine, the oak

-----the cactus, the mesquite

-----the violet, the rose

-----the fig, the grape-vine, the wheat

-----the corn, the thistle, the grass

-----the mushroom, the moss, the lichen, the algae,

-----the mold — all of the clans.

They taught us to touch, to fully delight in the here,

------to find contentment on the here.

We step in their tracks,

-----we walk on the sacred —

---------all our relations, all of the clans.

We walk, we step

-----in the tracks of our ancestors, our relations:

--------the granite, the sandstone

--------the jasper, the serpentine

--------the turquoise, the flint

--------the opal, the crystal

--------the agate, the jade

--------the gold, the iron

----the silver, the lead, the copper, the tin,

----boulder, pebble, sand, dust — all of the clans.

They taught us silence, quiet;

------they taught us to stay, to be.

We step in their track,

-----we walk on the sacred —

---------all our relations, all of the clans.

------It is dark; it is light —

here the roots of the Tree of Life,

------árbol de la vida, tree of Tamoanchan.

Look: wealth, treasure, our inheritance.

Look: teocuitatl, oro, gold, shit of the gods

-------chalchihuitl, jade, jade, the green stone

-------quetzalli, plumas, feathers, the precious things

-------xochitl, flores, the roots of flowers —

gifts and burdens,

------the useful, the hindering,

----------the dark medicine, the glittering poison.

Pick and choose: empowering joys there are,

--------------------useless sorrows there are;

needs true — clear and lovely as water

desires true — ruddy and joyous as wine;

--------needs false and deadly as arsenic

--------desires false and deadly as knives;

swords of jewels, plows muddied and dulled by stones;

--------dazzling powders, herbs rich in visions.

Choose and sort — it is not much you can carry.

Our ancestors, our relations make council; listen:

Much have our mothers, our fathers

-------our grandmothers, our grandfathers

-------our ancestors left us:

-----------gifts are there for our blessing

-----------debts are there for our curse.

Interroga a los ancianos — son sabios, son necios.

Question the ancients — they are wise, they are fools.

Señores míos, Señoras mías — my Lords, my Ladies,

---------¿Qué verdad dicen sus flores, sus cantos?

---------What truth do your flowers, your songs tell?

---------¿Són verdaderamente bellas, ricas sus plumas?

---------Are your feathers truly lovely, truly rich?

---------¿No es el oro sólo excremento de los dioses?

---------Is not gold only the excrement of the gods?

---------Sus jades, ¿son los más finos, los más verdes?

---------Your jades, are they the finest, the most green?

---------Su legado, ¿es tinta negra, tinta roja?

---------Your legacy, is it black ink, red ink?

They offer gifts, they give teachings:

------precious, worthless

------healing, dangerous —

sort, choose — choose the precious, the healing;

-----------------discard the worthless, the harmful;

------there is much to learn, there is much to unlearn.

Choose - each offers gifts, our ancestors, our relations —

---------human, animal, plant, mineral —

------------------they are us, our relations.

Choose and sort, sort and choose

---------these gifts are of the Earth, la Tierra

---------these gifts celebrate and nurture her

---------these gifts blaspheme and destroy her

---------------------These gifts are of the Earth.

Sort and choose, choose and sort.

-----The ancients are wise, the ancients are fools;

----------riches they gathered, garbage they hoarded.

Acepta sólo lo preciso; accept only the necessary:

--------lo que te haga amplio el corazón

--------what will widen your heart

--------lo que te ilumine el rostro

--------what will enlighten your face.

Pick and choose —

------hush —

--------------in silence sort and choose, sort and choose.

Hush —

----------Look carefully - have we chosen well?

the way back is hard, full of dread

----and much have our ancestors left us.

---------What of their gifts is worth the sharing?

----------------Consider well —

------------------------the gold and the jeweled sword

--------------------is not more than the work-dulled plow.

Consider, test your choice —

---------------------------------hush —

Tasks await us on the Earth for our healing, for hers —

-------difficult, great.

---------------Choose well for the journey, for the work.

hush —

---------remember:

----------------------joy is the root of our strength,

------------- the roots that feed us come from the heart

---------the science most wise disturbs least —

-----hush — hush — hush

So, we choose what we choose.

Remember: from these gifts we make our own;

--------------we add to the hoard.

-------Do not burden the children.

Do not carry so much we cannot hold each other’s hands.

----Remember: the most precious treasure

-----------------is that which we take for the giving.

We choose what we choose —

-----make ready — take up your bundle,

-----the seeds of our making - it is light, it is heavy;

-----precious are the bones of our ancestors;

-----leaving them buried makes them no less precious;

they are of the Earth, Madre Tierra, Coatlicue,

-----------------Pachi Mama, the Earth needs them.

------ehecatl, aire, air

------tletl, fuego, fire

------atl, agua, water

------tlalli, tierra, earth.

Make ready to leave the store house, the treasure;

walk round the cavern once as the clock turns

------from the East, red and gold with knowledge

------to the South yellow and green with love

------to the West black and blue with strength

------to the North white with healing.

You are now at the threshold — it is wide, it is narrow

-----------------------------------it is dark, it is light

-----------------------------------it is steep, it is plain.

Do not look back;

leave Mictlan, reino de la muerte, realm of the dead;

-------leave the cave of the ancients,

--------------the cave of our treasure;

------------------begin the way back.

What you bring back from the land of the dead,

-------from among the bones of the ancestors,

-------------is your gift to life.

---------------------Pray the gods you choose well.

Vuelve, vuelve, return.

It is your commitment,

-----the healing of yourself and the Earth.

What will you do?

-------How will you honor the ancestors?

-------------What will you say to the children?

--------------------What will you do for justice and peace?

Vuelve, vuelve, return.

Go, vete —

------------lleva la bendición de la vida;

------------------carry the blessing of life.

------------Go, vete —

form a face, form a heart.

forma un rostro, un corazón

in ixtli, in yollotl

Go, vete, go —

que los dioses te tengan, may the gods keep you.

In whatever you do, bendice la vida,

--------------pass on the blessing of life.

Vete y bendice la vida;

-----Go and pass on the blessing of life.

Vete, ha acabado; Go, the journey is finished —

Vete y empieza un día nuevo,

-----Go and begin a new day.

-----Vete, Go.

-

-

-

--

--Consejo para el peregrino a Mictlan

--Consejo para el peregrino a Mictlan------------------------(al modo Nahua)

Cruza el campo amarillo de cempoales,

baja al reino de las sombras;

es amplio, es estrecho.

Interroga a los ancianos;

son sabios, son necios:

— Señores míos, Señoras mías,

¿Qué verdad dicen sus flores, sus cantos?

¿Son verdaderamente bellas, ricas sus plumas?

¿No es el oro sólo excremento de los dioses?

Sus jades, ¿son los más finos, los más verdes?

Su legado, ¿es tinta negra, tinta roja? —

Acepta sólo lo preciso:

-----lo que te haga amplio el corazón

--------lo que te ilumine el rostro.

------------------------© Rafael Jesús González 2007

-----Advice for the Pilgrim to Mictlan

------------------- (in the Nahua mode)

Cross the yellow fields of marigolds,

descend to the realm of shadows;

it is wide, it is narrow.

Question the ancients;

they are wise, they are fools:

— My Lords, My Ladies,

What truth do your flowers, your songs tell?

Are your feathers truly lovely, truly rich?

Is not gold only the excrement of the gods?

Your jades, are they the finest, the most green?

Your legacy, is it black ink, red ink? —

Accept only the necessary:

-----what will widen your heart

----what will enlighten your face.

------------------------© Rafael Jesús González 2007

[Descent to Mictlan, Land of the Dead: Trance Poem in the Nahua mode (commissioned by the Oakland Museum of California while the author was Poet in Residence under a Writers on Site award by Poets & Writers, Inc. and a grant from The James Irvine Foundation in 1996) was written as a performance piece for voice, drums, didgeridoos, and movement intended to guide the audience upon an introspective journey of the imagination down into the kingdom of Death.

It is not so much entertainment as it is ritual art which, with the consent of each person in the audience to give himself or herself to their imagination, would induce the heightened perception of trance to descend into our collective and personal past to examine the legacy of our ancestors. What they have given us, we have become. It may be read by the attentive reader in the same way.

The times demand that we take stock of who we are, for our great Mother the Earth is wounded and, to heal her, we must heal ourselves, learn from the wisdom of our forebears and discard their mistakes. And in return for what each brings back from the store house of the past, each must make a commitment, in good faith, to change and to heal ourselves; and to care for and protect the Earth, all that she bears, and each other in brotherhood and sisterhood of the spirit and of the flesh. It is a gift and a blessing. Any less and we risk our own extinction on the Earth.]

Cruzad el campo amarillo de cempoales.

Cross the yellow fields of marigolds.

Bajad al reino de las sombras — es amplio, es estrecho.

Descend to the realm of shadows — it is wide, it is narrow.

We come to the mouth of the cavern of caverns,

realm of Mictlantecuhtli, Mictlancihuatl,

Señor-Señora Muerte, Our Lord, Our Lady of Death —

It is wide, it is narrow;

pasad, enter this chamber of yellow blooms,

--------the cempoalxochitl, the shield flower,

------------flor de muertos, flower of the Dead.

We step, we walk;

-----we walk the sacred;

---------every step is sacred.

We walk in the tracks of our ancestors,

we step in the tracks of the old ones,

----our grandmothers, our grandfathers,

----the ancients:

--------the people of the drum

--------the people of the canoe

--------the people of the pyramids

--------the people of the spear

--------the people of the shuttle and loom

--------the people of the sickle and plow,

------------our ancient ones, all of the clans.

They taught us to see;

they taught us not to see;

-----from them we learned to see;

-----------we learned not to see.

They taught us to dream;

------they taught us to fear;

-----------much to learn, much to unlearn.

We step in their tracks, we step on the sacred.

We walk, we step in the tracks of our ancestors,

----our relations:

---------the ocelot

---------the buffalo

---------the coyote

---------the bear

---------the salmon, the serpent, the eagle, the hawk,

---------monkey, turtle, frog,

---------the owl and the bat.

Further, further we walk:

the spider, the moth, the fly, the coral, the mite,

ameba, paramecium, germ, virus - all of the clans.

They taught us to see, to live in the now,

------to smell, to taste,

------to hear, to live in the now.

We step in their tracks,

-----we walk on the sacred —

---------all our relations, all of the clans.

We walk, we step in the tracks of our ancestors,

our relations:

-----the fern, the redwood

-----the pine, the oak

-----the cactus, the mesquite

-----the violet, the rose

-----the fig, the grape-vine, the wheat

-----the corn, the thistle, the grass

-----the mushroom, the moss, the lichen, the algae,

-----the mold — all of the clans.

They taught us to touch, to fully delight in the here,

------to find contentment on the here.

We step in their tracks,

-----we walk on the sacred —

---------all our relations, all of the clans.

We walk, we step

-----in the tracks of our ancestors, our relations:

--------the granite, the sandstone

--------the jasper, the serpentine

--------the turquoise, the flint

--------the opal, the crystal

--------the agate, the jade

--------the gold, the iron

----the silver, the lead, the copper, the tin,

----boulder, pebble, sand, dust — all of the clans.

They taught us silence, quiet;

------they taught us to stay, to be.

We step in their track,

-----we walk on the sacred —

---------all our relations, all of the clans.

------It is dark; it is light —

here the roots of the Tree of Life,

------árbol de la vida, tree of Tamoanchan.

Look: wealth, treasure, our inheritance.

Look: teocuitatl, oro, gold, shit of the gods

-------chalchihuitl, jade, jade, the green stone

-------quetzalli, plumas, feathers, the precious things

-------xochitl, flores, the roots of flowers —

gifts and burdens,

------the useful, the hindering,

----------the dark medicine, the glittering poison.

Pick and choose: empowering joys there are,

--------------------useless sorrows there are;

needs true — clear and lovely as water

desires true — ruddy and joyous as wine;

--------needs false and deadly as arsenic

--------desires false and deadly as knives;

swords of jewels, plows muddied and dulled by stones;

--------dazzling powders, herbs rich in visions.

Choose and sort — it is not much you can carry.

Our ancestors, our relations make council; listen:

Much have our mothers, our fathers

-------our grandmothers, our grandfathers

-------our ancestors left us:

-----------gifts are there for our blessing

-----------debts are there for our curse.

Interroga a los ancianos — son sabios, son necios.

Question the ancients — they are wise, they are fools.

Señores míos, Señoras mías — my Lords, my Ladies,

---------¿Qué verdad dicen sus flores, sus cantos?

---------What truth do your flowers, your songs tell?

---------¿Són verdaderamente bellas, ricas sus plumas?

---------Are your feathers truly lovely, truly rich?

---------¿No es el oro sólo excremento de los dioses?

---------Is not gold only the excrement of the gods?

---------Sus jades, ¿son los más finos, los más verdes?

---------Your jades, are they the finest, the most green?

---------Su legado, ¿es tinta negra, tinta roja?

---------Your legacy, is it black ink, red ink?

They offer gifts, they give teachings:

------precious, worthless

------healing, dangerous —

sort, choose — choose the precious, the healing;

-----------------discard the worthless, the harmful;

------there is much to learn, there is much to unlearn.

Choose - each offers gifts, our ancestors, our relations —

---------human, animal, plant, mineral —

------------------they are us, our relations.

Choose and sort, sort and choose

---------these gifts are of the Earth, la Tierra

---------these gifts celebrate and nurture her

---------these gifts blaspheme and destroy her

---------------------These gifts are of the Earth.

Sort and choose, choose and sort.

-----The ancients are wise, the ancients are fools;

----------riches they gathered, garbage they hoarded.

Acepta sólo lo preciso; accept only the necessary:

--------lo que te haga amplio el corazón

--------what will widen your heart

--------lo que te ilumine el rostro

--------what will enlighten your face.

Pick and choose —

------hush —

--------------in silence sort and choose, sort and choose.

Hush —

----------Look carefully - have we chosen well?

the way back is hard, full of dread

----and much have our ancestors left us.

---------What of their gifts is worth the sharing?

----------------Consider well —

------------------------the gold and the jeweled sword

--------------------is not more than the work-dulled plow.

Consider, test your choice —

---------------------------------hush —

Tasks await us on the Earth for our healing, for hers —

-------difficult, great.

---------------Choose well for the journey, for the work.

hush —

---------remember:

----------------------joy is the root of our strength,

------------- the roots that feed us come from the heart

---------the science most wise disturbs least —

-----hush — hush — hush

So, we choose what we choose.

Remember: from these gifts we make our own;

--------------we add to the hoard.

-------Do not burden the children.

Do not carry so much we cannot hold each other’s hands.

----Remember: the most precious treasure

-----------------is that which we take for the giving.

We choose what we choose —

-----make ready — take up your bundle,

-----the seeds of our making - it is light, it is heavy;

-----precious are the bones of our ancestors;

-----leaving them buried makes them no less precious;

they are of the Earth, Madre Tierra, Coatlicue,

-----------------Pachi Mama, the Earth needs them.

------ehecatl, aire, air

------tletl, fuego, fire

------atl, agua, water

------tlalli, tierra, earth.

Make ready to leave the store house, the treasure;

walk round the cavern once as the clock turns

------from the East, red and gold with knowledge

------to the South yellow and green with love

------to the West black and blue with strength

------to the North white with healing.

You are now at the threshold — it is wide, it is narrow

-----------------------------------it is dark, it is light

-----------------------------------it is steep, it is plain.

Do not look back;

leave Mictlan, reino de la muerte, realm of the dead;

-------leave the cave of the ancients,

--------------the cave of our treasure;

------------------begin the way back.

What you bring back from the land of the dead,

-------from among the bones of the ancestors,

-------------is your gift to life.

---------------------Pray the gods you choose well.

Vuelve, vuelve, return.

It is your commitment,

-----the healing of yourself and the Earth.

What will you do?

-------How will you honor the ancestors?

-------------What will you say to the children?

--------------------What will you do for justice and peace?

Vuelve, vuelve, return.

Go, vete —

------------lleva la bendición de la vida;

------------------carry the blessing of life.

------------Go, vete —

form a face, form a heart.

forma un rostro, un corazón

in ixtli, in yollotl

Go, vete, go —

que los dioses te tengan, may the gods keep you.

In whatever you do, bendice la vida,

--------------pass on the blessing of life.

Vete y bendice la vida;

-----Go and pass on the blessing of life.

Vete, ha acabado; Go, the journey is finished —

Vete y empieza un día nuevo,

-----Go and begin a new day.

-----Vete, Go.

© Rafael Jesús González 2008

-

--

Saturday, November 1, 2008

Feast of All Saints (to make an ofrenda)

-

A la memoria de Louis "Studs" Terkel (16 mayo 1912 – 31 octubre 2008) siempre luchador por la justicia con todo su intelecto, con todo el corazón. Tomemos todos su antorcha.

To the memory of Louis "Studs" Terkel (May 16, 1912 – October 31, 2008) always a fighter for justice with all his intellect, with all his heart. Let us all take up his torch.

El corazón de la muerte ~ The Heart of Death

-------ofrenda a los difuntos --------------- offering to the dead

---------al modo nahua------- / --------------in the Nahua mode

---Le hacemos, formamos

---el corazón a la muerte —

---We make, we form

---the heart of death —

de flores

de flores amarillas,

del cempoalxochitl —

of flowers

of yellow flowers

of marigolds —

de agua

de agua clara,

consuelo de la sed —

of water

of clear water

comfort of thirst —

de pan

de maíz, de trigo

nuestro sustento —

of bread

of corn, of wheat

our sustenance —

de comida y bebida

de comida y bebida

de nuestro alimento

que da deleite al paladar —

of food & drink

of our nutrition

that gives the palate delight —

de luz

de luz

de luz que alumbra el camino

anhelo de mariposas

-------------------nocturnas —

of light

of light that shows the way

desire of night moths —

de calaveras de azúcar

de calaveras de azúcar

de calaveras dulces

como la vida fugaz —

of sugar skulls

of candy skulls

sweet as fleeting life —

de copal, artemisa,

incienso, humo perfumado

que invoca a los dioses —

of copal, sage,

incense, perfumed smoke

that invokes the gods —

de flor y canto

de flor y canto le hacemos

el corazón a la muerte.

of flower & song

of flower & song we make

the heart of death.

-------------------------------------© Rafael Jesús González 2008

-

-

A la memoria de Louis "Studs" Terkel (16 mayo 1912 – 31 octubre 2008) siempre luchador por la justicia con todo su intelecto, con todo el corazón. Tomemos todos su antorcha.

To the memory of Louis "Studs" Terkel (May 16, 1912 – October 31, 2008) always a fighter for justice with all his intellect, with all his heart. Let us all take up his torch.

El corazón de la muerte ~ The Heart of Death

-------ofrenda a los difuntos --------------- offering to the dead

---------al modo nahua------- / --------------in the Nahua mode

---Le hacemos, formamos

---el corazón a la muerte —

---We make, we form

---the heart of death —

de flores

de flores amarillas,

del cempoalxochitl —

of flowers

of yellow flowers

of marigolds —

de agua

de agua clara,

consuelo de la sed —

of water

of clear water

comfort of thirst —

de pan

de maíz, de trigo

nuestro sustento —

of bread

of corn, of wheat

our sustenance —

de comida y bebida

de comida y bebidade nuestro alimento

que da deleite al paladar —

of food & drink

of our nutrition

that gives the palate delight —

de luz

de luzde luz que alumbra el camino

anhelo de mariposas

-------------------nocturnas —

of light

of light that shows the way

desire of night moths —

de calaveras de azúcar

de calaveras de azúcarde calaveras dulces

como la vida fugaz —

of sugar skulls

of candy skulls

sweet as fleeting life —

de copal, artemisa,

incienso, humo perfumado

que invoca a los dioses —

of copal, sage,

incense, perfumed smoke

that invokes the gods —

de flor y canto

de flor y canto le hacemos

el corazón a la muerte.

of flower & song

of flower & song we make

the heart of death.

-------------------------------------© Rafael Jesús González 2008

-

-

Friday, October 31, 2008

Halloween

-

- - ---------Trick & Treat

Death at the door,

----or lurking among the leaves,

death itself is the inevitable trick;

the only treat worth the having,

----to love fearlessly,

------------------------and well.

-------© Rafael Jesús González 2008

(The Montserrat Review, Issue 7, Spring 2003;

author’s copyrights)

-----------Chasco y Regalo

-----------Chasco y Regalo

La muerte a la puerta,

----o en emboscada entre la hojas,

la muerte misma es el chasco inevitable;

el único regalo que vale la pena,

-----amar sin temor,

------------------------y amar bien.

---------------© Rafael Jesús González 2008

In the Western cultures and in the cultures of Meso-America, we come to the Feast of Samhain (sa-win), Feast of All Souls, Día de muertos, in which we render honor to the dead, those who have crossed to that vast realm to which we all that live are destined.

How shall we best honor them who gave us life, whom we loved, or whom we never knew but whose gifts, and curses, we carry in our genes from since the very roots of our species in ancient Africa, and beyond?

In this nation of the United States, and by extension, the world, we have come to our moment of truth. In essence the contention, the choice is between a wide-hearted spirit of compassion, of justice, of care for one another, and respect for the Earth on the one hand and a narrow-hearted spirit of meanness, of unjust privilege, of disregard for one another, and abuse of the Earth on the other. One choice is founded on hope and optimism and adherence to our highest ideals, the other on fear and cynicism and willingness to sacrifice the very freedoms for which we once prided ourselves, and the Earth itself.

By what choices we make, what votes we cast we will declare ourselves in one camp or the other. Our myths in the West no longer serve us and it is up to us to honor our dead by honoring life with compassion and love or dishonoring them by choosing the road to extinction through fear and disregard for one another and for the Earth itself.

May we choose wisely and truly honor our dead by honoring one another, life, and the Earth that bears it.

En las culturas occidentales y en las culturas de Mezo-América, llegamos a la Fiesta de Samhain (sa-huin), Fiesta de todas las ánimas, Día de muertos, en las cuales rendimos honor a los muertos, los que han cruzado al vasto reino al cual todos los que vivimos somos destinados.

¿Cómo mejor honrar a los que nos dieron la vida, a quienes amamos, o a quienes jamás conocimos pero de quienes dones, y maldiciones, llevamos en nuestros genes desde las meras raíces de nuestra especie en la África antigua y más allá?

En esta nación de los Estados Unidos, y por extensión el mundo, hemos llegado a nuestro momento de la verdad. En esencia la contienda, la opción es entre un espíritu compasivo de amplio corazón, de justicia, de amor uno por el otro y respeto a la Tierra en una mano y un espíritu estrecho y mezquino de privilegio injusto, de falta de respeto uno al otro y abuso de la Tierra en la otra. Una opción se basa en la esperanza y el optimismo y adherencia a nuestros más altos ideales, la otra en el temor y el cinismo y una disposición a sacrificar las meras libertades de las cuales una vez nos enorgullecíamos y la Tierra misma.

Por cual opción tomamos, por cuales votos hagamos, nos declararemos en un campo o el otro. Nuestros mitos en el Occidente ya no nos sirven y queda en nosotros honrar a nuestros muertos honrando la vida con compasión y amor o deshonrándolos optando por un camino hacia la extinción por temor y falta de respeto uno hacia al otro y hacia la tierra misma.

Que optemos sabiamente y verdaderamente honremos a nuestros muertos honrándonos unos a los otros, a la vida y a la Tierra que la engendra.

-

-

-

- - ---------Trick & Treat

Death at the door,

----or lurking among the leaves,

death itself is the inevitable trick;

the only treat worth the having,

----to love fearlessly,

------------------------and well.

-------© Rafael Jesús González 2008

(The Montserrat Review, Issue 7, Spring 2003;

author’s copyrights)

-----------Chasco y Regalo

-----------Chasco y RegaloLa muerte a la puerta,

----o en emboscada entre la hojas,

la muerte misma es el chasco inevitable;

el único regalo que vale la pena,

-----amar sin temor,

------------------------y amar bien.

---------------© Rafael Jesús González 2008

In the Western cultures and in the cultures of Meso-America, we come to the Feast of Samhain (sa-win), Feast of All Souls, Día de muertos, in which we render honor to the dead, those who have crossed to that vast realm to which we all that live are destined.

How shall we best honor them who gave us life, whom we loved, or whom we never knew but whose gifts, and curses, we carry in our genes from since the very roots of our species in ancient Africa, and beyond?

In this nation of the United States, and by extension, the world, we have come to our moment of truth. In essence the contention, the choice is between a wide-hearted spirit of compassion, of justice, of care for one another, and respect for the Earth on the one hand and a narrow-hearted spirit of meanness, of unjust privilege, of disregard for one another, and abuse of the Earth on the other. One choice is founded on hope and optimism and adherence to our highest ideals, the other on fear and cynicism and willingness to sacrifice the very freedoms for which we once prided ourselves, and the Earth itself.

By what choices we make, what votes we cast we will declare ourselves in one camp or the other. Our myths in the West no longer serve us and it is up to us to honor our dead by honoring life with compassion and love or dishonoring them by choosing the road to extinction through fear and disregard for one another and for the Earth itself.

May we choose wisely and truly honor our dead by honoring one another, life, and the Earth that bears it.

En las culturas occidentales y en las culturas de Mezo-América, llegamos a la Fiesta de Samhain (sa-huin), Fiesta de todas las ánimas, Día de muertos, en las cuales rendimos honor a los muertos, los que han cruzado al vasto reino al cual todos los que vivimos somos destinados.

¿Cómo mejor honrar a los que nos dieron la vida, a quienes amamos, o a quienes jamás conocimos pero de quienes dones, y maldiciones, llevamos en nuestros genes desde las meras raíces de nuestra especie en la África antigua y más allá?

En esta nación de los Estados Unidos, y por extensión el mundo, hemos llegado a nuestro momento de la verdad. En esencia la contienda, la opción es entre un espíritu compasivo de amplio corazón, de justicia, de amor uno por el otro y respeto a la Tierra en una mano y un espíritu estrecho y mezquino de privilegio injusto, de falta de respeto uno al otro y abuso de la Tierra en la otra. Una opción se basa en la esperanza y el optimismo y adherencia a nuestros más altos ideales, la otra en el temor y el cinismo y una disposición a sacrificar las meras libertades de las cuales una vez nos enorgullecíamos y la Tierra misma.

Por cual opción tomamos, por cuales votos hagamos, nos declararemos en un campo o el otro. Nuestros mitos en el Occidente ya no nos sirven y queda en nosotros honrar a nuestros muertos honrando la vida con compasión y amor o deshonrándolos optando por un camino hacia la extinción por temor y falta de respeto uno hacia al otro y hacia la tierra misma.

Que optemos sabiamente y verdaderamente honremos a nuestros muertos honrándonos unos a los otros, a la vida y a la Tierra que la engendra.

~ Rafael Jesús González

-

-

-

Sunday, October 26, 2008

Mexico's Día de Muertos through the centuries

--

Awed by the eternal cycle of life and death and the need of sacrifice to assure the continuation of life, ages before the Spaniards came to the Americas, the peoples of ancient Mexico, particularly the Nahuas, of which the Mexica (generally called Aztecs) formed a part, celebrated the dead in a great feast quite different from the one we know today. It began on August 8, by the European calendar, and they called it Micailhuitontli, Small Feast of the Dead, to honor their dead children. On that morning, the people went to the forest and cut down a tall, straight tree which they brought to the gates of the city. There, for twenty days, they blessed the tree and stripped it of its bark.

Awed by the eternal cycle of life and death and the need of sacrifice to assure the continuation of life, ages before the Spaniards came to the Americas, the peoples of ancient Mexico, particularly the Nahuas, of which the Mexica (generally called Aztecs) formed a part, celebrated the dead in a great feast quite different from the one we know today. It began on August 8, by the European calendar, and they called it Micailhuitontli, Small Feast of the Dead, to honor their dead children. On that morning, the people went to the forest and cut down a tall, straight tree which they brought to the gates of the city. There, for twenty days, they blessed the tree and stripped it of its bark.

During those twenty days, they did ritual, sacrificed, feasted, danced, and made offerings to the dead of cempoalxochitl flowers, fire, copal, food, and drink. Then, on August 28, which they called Huey Micailhuitl (Great Feast of the Dead), in honor of their adult dead, they made a large figure of a bird perched on flowering branches out of amaranth seed dough, painted it brightly, and decorated it with colorful feathers. They fixed the dough bird to the end of the tree trunk, raised it in the courtyard of the Great Temple, and honored it with more offerings, singing, copal, dances, sacrifice, and bloodletting.

One hour before sunset, the young noblemen climbed the pole to bring down the figure of the bird. The youths who reached the top first and brought down the dough figure were much honored. They broke it up and passed it out among the people to eat; they called it “flesh of the god.” Then they brought down the pole and broke it up, and everyone tried to take a piece of it back to their homes because it was holy.

The pole and its god-bird on flowering branches must have stood for the mythical Tree of Life that grew in the earthly paradise of Tamoanchan. The blood of sacrifice nourished the Tree of Life, just as Quetzalcoatl, Plumed Serpent, God of Life, shed his blood to create humankind. The ritual of the pole and the flesh of the god honored the fact that life cannot be separated from death; we live and die, and our deaths are the price of living.

Composed of both joy and pain, life is brief and uncertain, its end a question that disquiets the heart. Many poems addressing this sad truth were composed by the Nahua poets, the most famous of whom was Nezahualcoyotl, King of Texcoco, who said:

------------------Is it true that one lives on earth?

------------------Perhaps forever on the earth?

------------------Only a brief instant here!

------------------Even the precious stones chip away,

------------------even the gold falls apart,

------------------even the precious feathers tear.

------------------Perhaps forever on the earth?

------------------Only a brief instant here!